Safely managed sanitation to protect our groundwater

Since 1993, the world has been celebrating World Water Day every 22 March. This year’s theme is ‘Groundwater, making the invisible, visible.’ It raises the alarm for growing global concern over the need to protect groundwater – the source of almost all liquid freshwater in the world – from further contamination, due to increasing population, urbanisation, industrialisation, and agriculture.

As more people all over the world gain access to a toilet that is not connected to a sewerage system, it is critical to ensure proper containment of human waste to minimise the threat of groundwater contamination. In making the invisible groundwater visible, it is important to also unpeel the layers of invisibility that lead to groundwater contamination – this includes poorly designed, constructed, and operated onsite sanitation facilities.

In this blog, I share some key points from SNV’s ongoing multi-stakeholder learning processes and practical research on safely managed sanitation in rural Bhutan and Lao PDR.

In 2020, one in four people (2 billion people) lacked safely managed drinking water at their home. At current rates of progress, 1.6 billion people will remain without safely managed drinking water services by 2030. The situation for sanitation is even bleaker with nearly half the world’s population (3.6 billion people) lacking safely managed sanitation services in 2020.

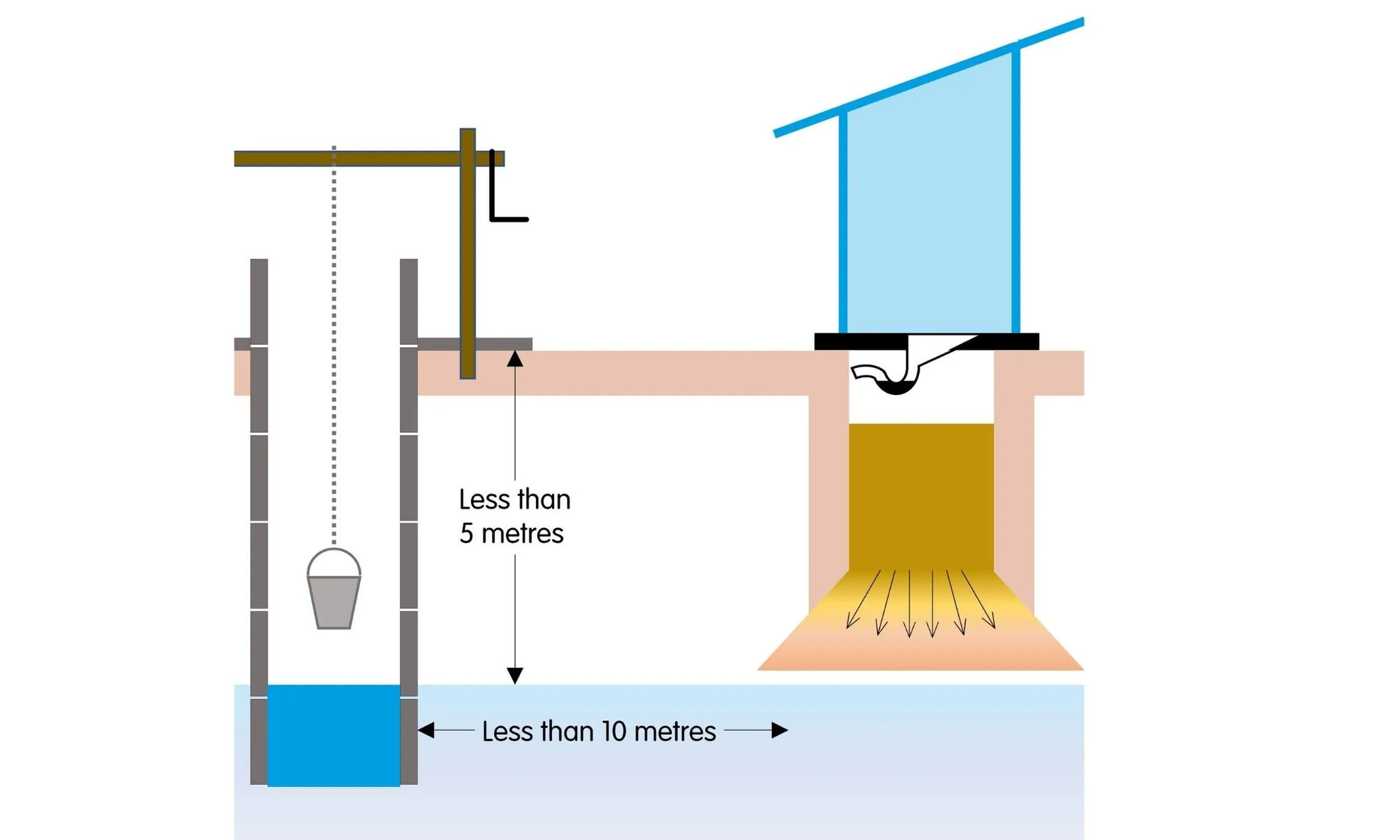

Poorly managed sanitation and inappropriate sanitation technologies can pollute our water sources. In the absence of sewer connections, toilets rely on onsite storage facilities in the form of pits or (septic) tanks – usually located below ground level to which the toilet is connected – to separate human waste from people. Oftentimes, the selection of these types of toilets does not adequately consider the likelihood of groundwater contamination.

The importance of safe siting of pit latrines to avoid groundwater pollution

Keeping groundwater safe from human waste

As part of the Sustainable Sanitation and Hygiene for All (SSH4A) programme, SNV documented its latest insights and learning on rural sanitation in Bhutan and Lao PDR. The documentation explores existing regulatory frameworks around faecal waste management, faecal sludge accumulation rates, and associated pit filling rates in their respective contexts.

Several key points emerged from this research:

Consider the presence or absence of pit emptying services when selecting the type of toilet to be constructed or installed. For example, toilet designs that require frequent emptying in areas where professional pit emptying services do not exist (or will not be available in the foreseeable future) should not be actively promoted.

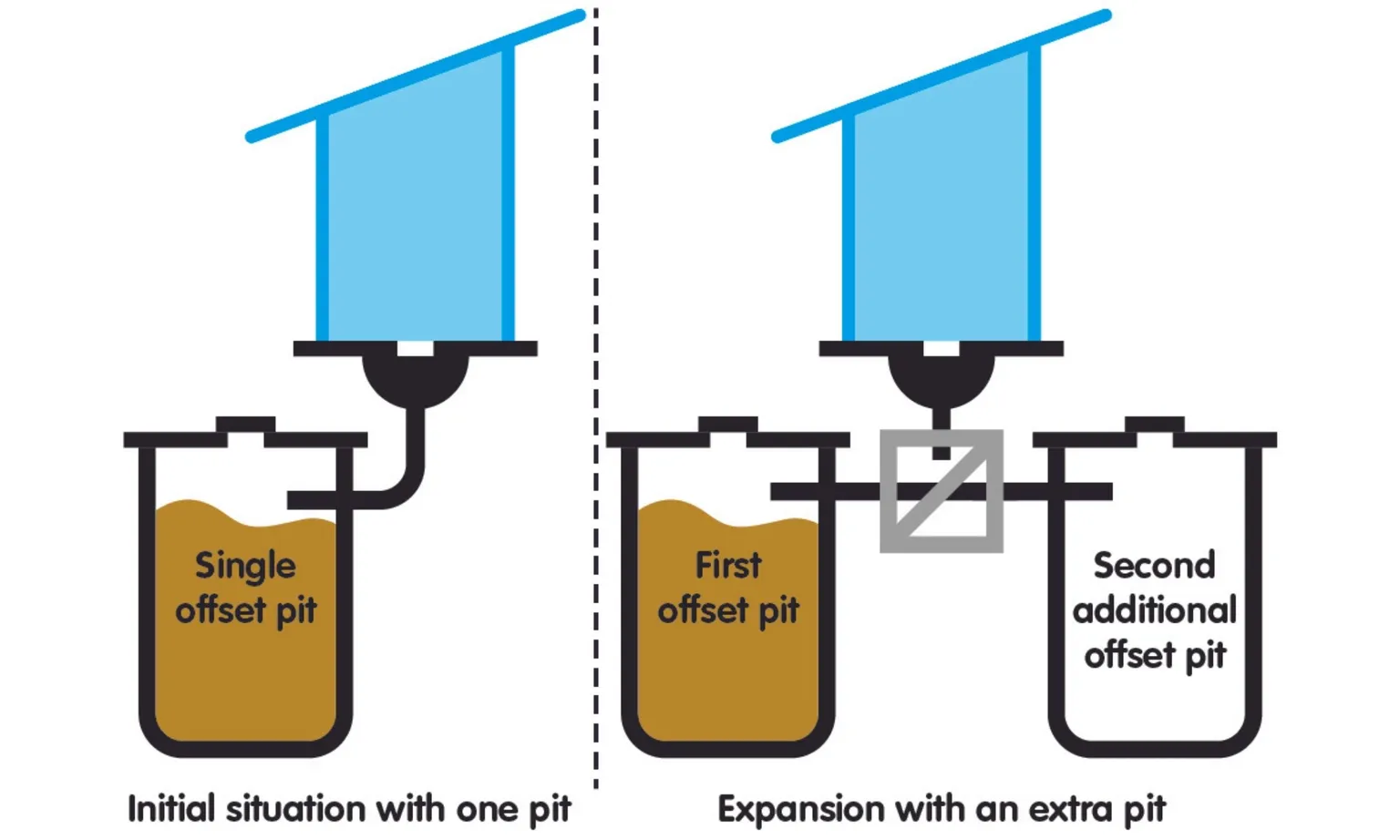

Promote toilet designs that meet basic sanitation criteria, but that over time, can be easily upgraded to meet safely managed sanitation criteria. For example, as long as there is enough space, a toilet with a single pit can be easily upgraded by adding a second pit at a later stage. In this way initial investment costs are more manageable as costs are kept low.

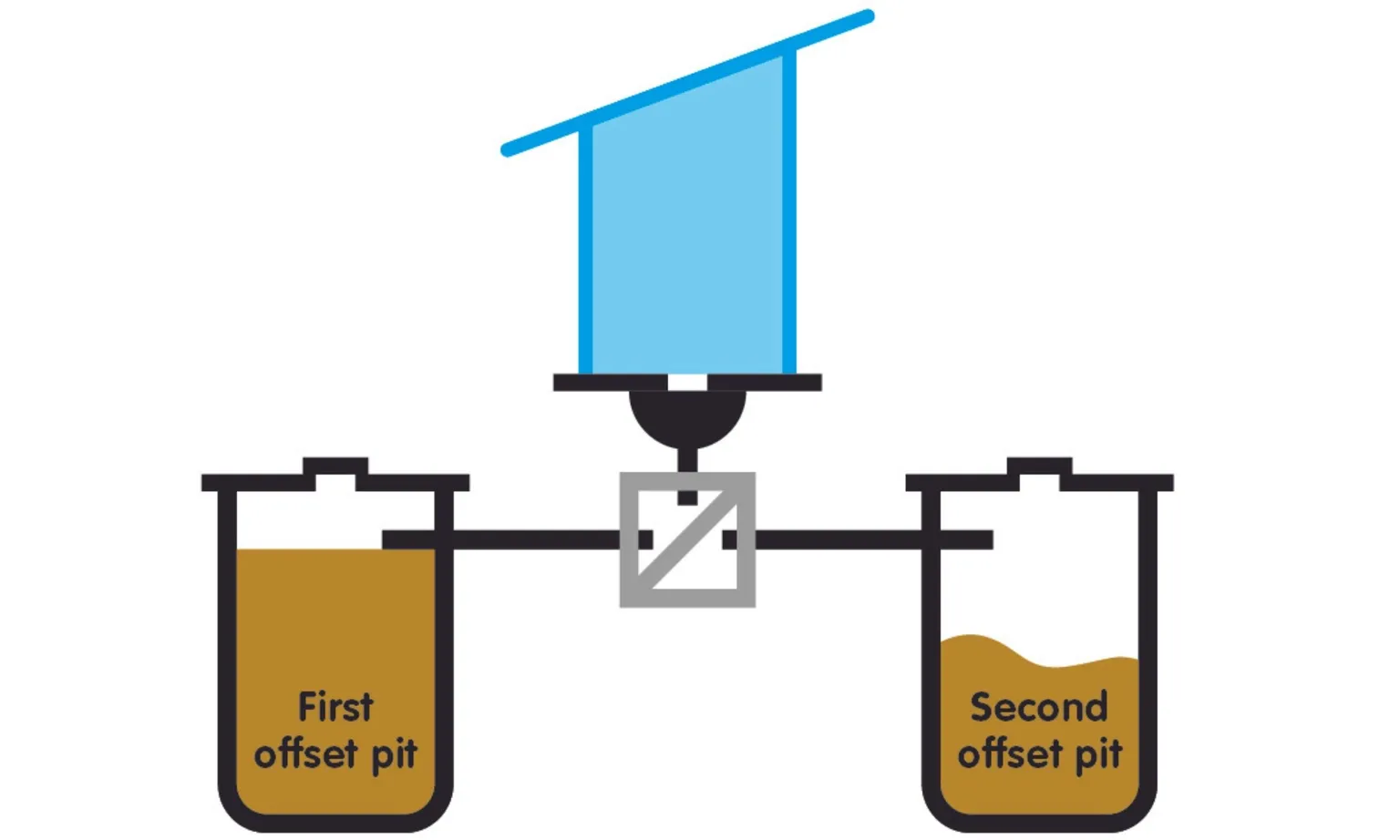

Encourage construction of alternative toilet designs, such as alternating twin pits, that can be safely emptied by owners. This is particularly appropriate in rural communities where professional pit emptying services are not available or affordable. Because self-emptied pits are relatively shallow, an additional advantage here is that the risk of groundwater contamination is reduced.

Pit upgradation/expansion (on right)

Double alternating offset pit

A simple, but effective methodology for informed choice

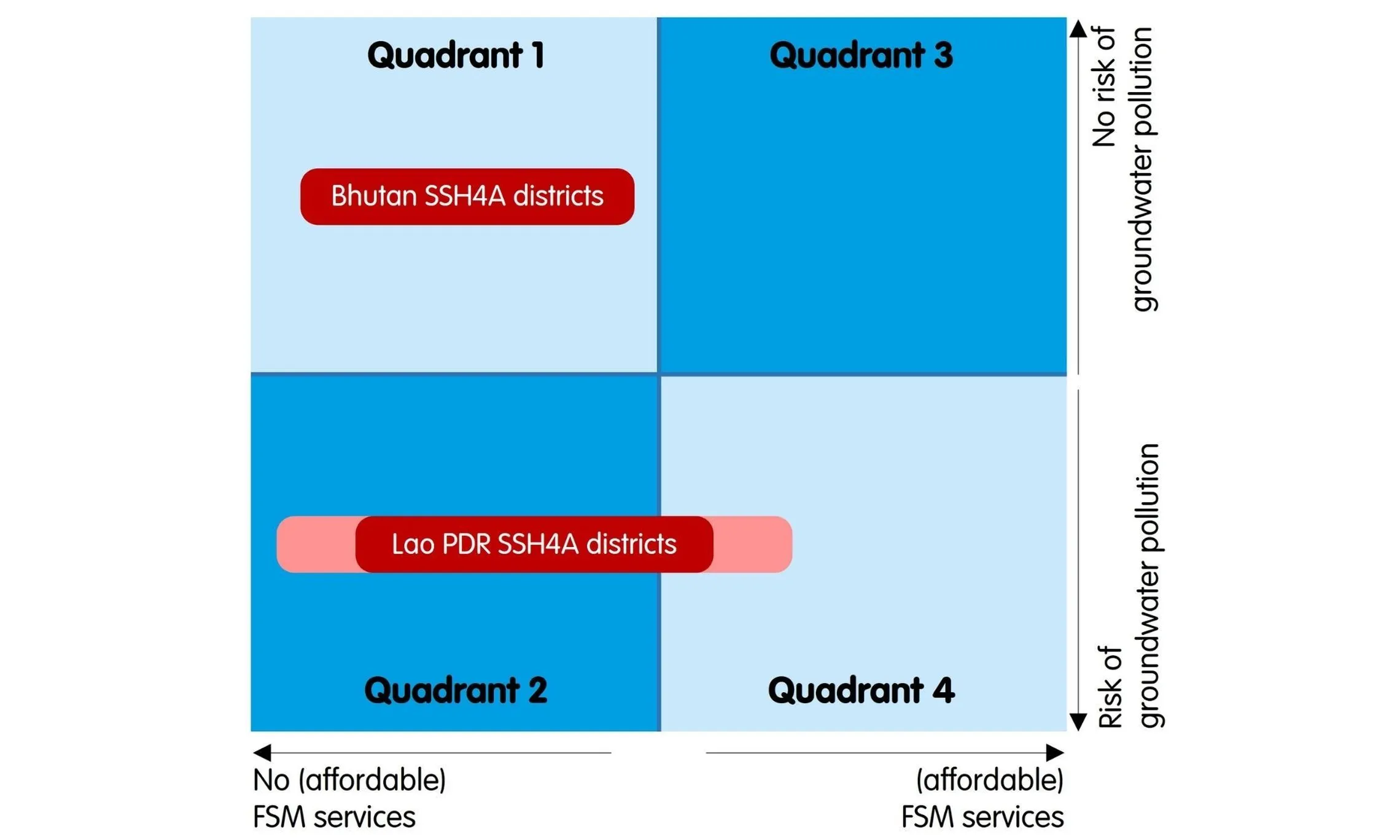

The research provides a simple methodology to support the selection of a suitable onsite sanitation technology. Alongside consumer considerations such as affordability and individual preferences, two critical determinants offer important insights into making an informed choice. These are:

Risk of groundwater pollution; and the

Availability of (affordable) pit emptying services.

Based on practical research and lessons learnt, the approach to realising safely managed sanitation in this context is to avoid making pit emptying an afterthought or only when a pit or tank is about to fill up or overflow. From the start, plan accordingly. Hence, the application of the pit emptying services versus groundwater pollution risk matrix can provide important insights in the decision-making process.

Pit emptying services vs groundwater pollution risk matrix

Other factors to consider in the decision-making process and an overview of the types of onsite sanitation technologies per quadrant are outlined in the learning papers.

What else?

It takes more than just a few smart (or appropriate) technology options to achieve safely managed sanitation. The learning papers list other crucial elements of the WASH system that will require strengthening to ensure adequate and equitable sanitation for all by 2030. Think of changes to policies and legislation, improved service level monitoring, changing user behaviour and practices, and so on.

Author: Erick Baetings, Sanitation Specialist, IRC WASH

Photo: Alternating twin pit construction in Bhutan (SNV/Tashi Dorji)

More information:

[1] This blog was written based on lessons learnt from SNV's sanitation research in rural Bhutan and Lao PDR. Access the learning papers here: Realising safely managed sanitation in Bhutan and Realising safely managed sanitation in Lao PDR.

[2] Ongoing SNV WASH research and learning processes in Bhutan and Lao PDR are supported by the Australian Government’s Water for Women Fund.

[3] For more information on SNV's work and practical research in Bhutan and Lao PDR, contact Gabrielle Halcrow, Multi-country programme manager of the Beyond the Finish Line programme by email.

There's more to the tech

Beyond searching for appropriate sanitation technologies, there are other considerations to take to keep our groundwater safe. The 'human factor' plays a key role - whether it is in improving governance or enabling better management and service performance.