How to deliver containments that protect our groundwater

The structural integrity of toilet containments and their maintenance matter. When leaks occur or containments overflow, we put our groundwater at risk of contamination. Treating contaminated groundwater is 10 to 30 times more expensive than taking preventative steps, such as advancing the roll-out of environmentally safe toilets.

Similar to groundwater, containments – as discussed in this podcast – are located underneath the ground and are out of sight. As a 2021 SNV survey validated, toilet user experience and perceptions were influenced largely by parts of our toilets that can be seen and held. Sanitation investments and planning were no different as most focused on quick wins or those that facilitated easy attribution: the number of toilets constructed, emptying and transport, treatment, and reuse technologies.

Attention to containments was limited; even when failing containments – located at the start of the sanitation chain – disrupted the entire sanitation service and posed great risks for ground water contamination.

The place of groundwater safety in addressing the sanitation crisis

The world’s sanitation goal is unlikely to be achieved by 2030, sounding the alarm bells to deliver to this commitment at greater speed. As we search for viable ways to address the sanitation crisis, it is imperative to consider how containments have an impact on our groundwater.

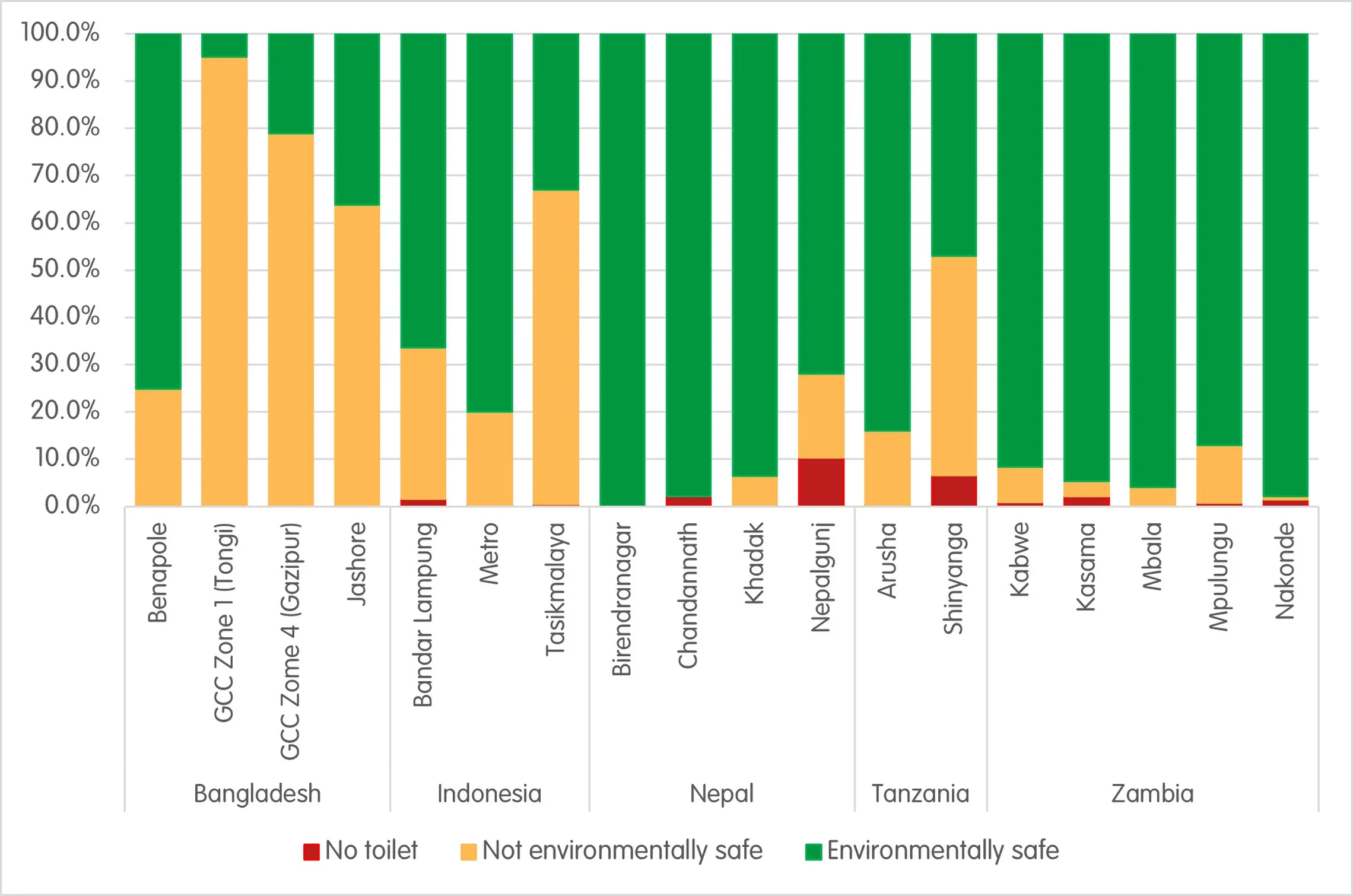

SNV city data on on sanitation status based on soil type, toilet siting, and groundwater depth, 2021

How to deliver groundwater-safe containments?

Below are some points to consider based on SNV’s experience implementing its urban sanitation programmes - WASH SDG and CWISE - across 20 cities in five countries.

Select site-, soil-, and groundwater-appropriate toilets. It is tempting and often cheaper to select one toilet technology for an area-wide toilet development project, but this is highly discouraged. Before selecting a toilet, consider the type of containment it uses, and examine the groundwater level and type of soil in the area.

Toilet catalogues that offer a suite of technologies, complete with information on (i) containment building or upgradation operational costs, and (ii) applicability/appropriateness across different locations help guide investments in the direction of containments that are safe to construct.

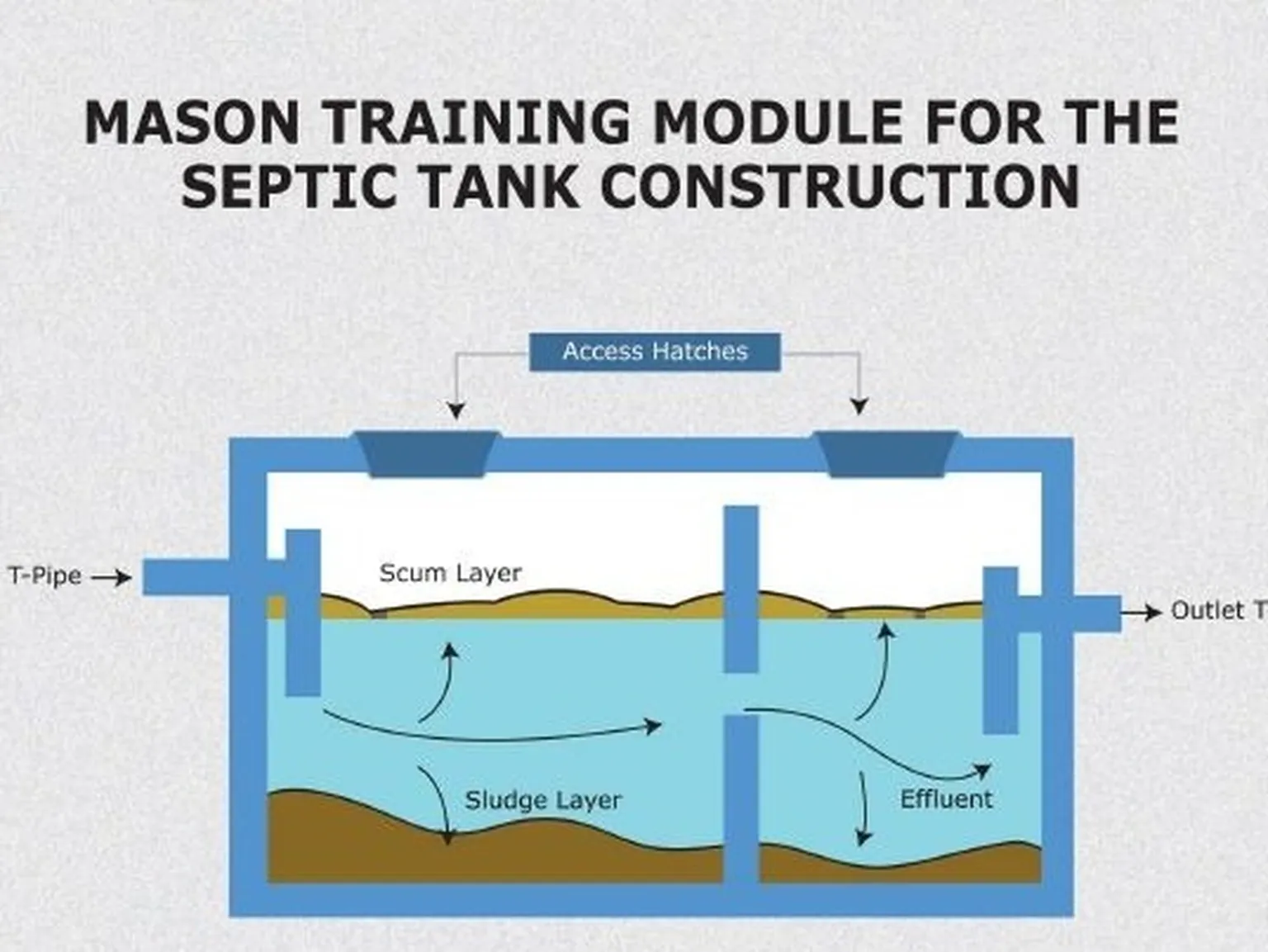

Introduce and enforce compliance standards for septic tanks in urban areas. Septic tanks are predominantly used in cities, but many fail to meet safety standards. Though it is widely recognised that a septic tank is an integral part for on-site safe sanitation, what is meant by a ‘proper septic tank’ is not well-understood or implemented by community, planners, engineers, and policy makers.

In most cases, septic tank owners rely on masons’ ingenuity to manage effluent, such as setting up bottomless tanks, oversized tanks, and direct connections into the nearest drains, which while slowing down the fill rate of containments, poses great threat to groundwater. Moreover, accountability mechanisms to ensure that the appropriate systems are selected require reinforcement. For instance, even if sanitation system detailed plans are required for the build approval process, these plans are not always followed through or monitored during construction. Making national building codes more robust and training relevant building inspectors and design consultants/contractors are important safety nets to consider.

Institutionalise capacity building activities for masons and contractors. Improper designs harm the immediate living environment, the population, and put sanitation workers who empty tanks at serious safety and health risk. With partner masons, SNV identified several flaws in septic tanks that require upgradation, e.g., the ratio of breadth and length, misaligned hydraulic profiles, improper positioning of baffle wall, missing T-traps at inlet and outlet, inappropriate or faulty sewer holes, and missing soak wells.

It is therefore necessary to strengthen masons’ and contractors’ understanding of, (i) the design parameters to implement based on qualitative and quantitative considerations for volume of wastewater, hydraulic retention time, desludging period, and temperature, for example, and (ii) technology option cost, size, work efficiency, and related risks. Documentation of these parameters in training modules help to inform upgradation investments and future toilet construction. Institutionalising professional trainings for masons on septic tank construction ensures that masons gain the appropriate information and skills to deliver to nationally recognised safety standards.

Formalise and professionalise the work of sanitation workers. Formalising the work of masons and emptiers through government-approved licensing and certification procedures does not only lift the status of sanitation workers but makes the entire sanitation service chain more robust. Beyond lifting worker’s skills and know-how, they too must be made accountable for the quality of their work, must be reachable to consumers (e.g., create a database of masons and emptiers managed by local authorities), and must be protected while on the job (e.g., developing SOPs for occupational health and safety).

Intensify the safe containment conversation now

A failure at the start of the chain – in this case, containments – has an impact on the entire sanitation service delivery. But beyond sanitation, poorly constructed and maintained containments heightens the potential for groundwater contamination. As this article suggested, the links between addressing the sanitation challenge and ensuring safer groundwater cannot be disputed and must be addressed.

Author: Rajeev Munankami, SNV Multi-country Programme Manager, WASH SDG programme. Interested to continue the conversation with SNV, email Rajeev with your ideas or queries.

Banner photo: Masons in Indonesia during an SNV-led practical workshop on septic tank installation (SNV in Indonesia)

More information:

[1] This article shares key learning from SNV’s WASH SDG (urban) programme Performance monitoring reviews 2017 and 2021.

[2] Worldwide, over 2 billion people still do not have access to clean drinking water and 3.6 billion can’t (safely) access a toilet. The WASH SDG Programme is a six-year programme that works on improving access to, and use of, safe drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene in seven countries in Africa and Asia. The collaboration consists of SNV, WASH Alliance International and Plan International, and is financed by the Netherlands’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Within the programme, special attention is given to gender and social inclusion, climate vulnerability, and resilience. We work with local partners to achieve sustainable change.

[3] Safe containments are also a priority topic for SNV’s water and sanitation efforts in rural areas. Interesting insights on safely managed sanitation are available, with a focus on Bhutan and Lao PDR.

Groundwater pollution in rural areas?

With many more households gaining a connection to a toilet, the accumulation of human waste in pits and/or septic tanks is inevitable. The failure to prevent sludge seepage into the groundwater will have negative consequences to our water security.