Why invest on more durable materials for sanitation facilities now?

On average, Kabwe’s sanitation facilities only last for two years, finds an SNV urban sanitation study. In this blog, we present our research findings on the durability of sanitation facilities in Kabwe, Zambia and the willingness of households (and property developers) to pay for sanitation facility upgrades.

More than 80% of people in Kabwe use onsite sanitation facilities,[1] meaning they depend on pits and septic tanks. Of these onsite sanitation facilities, 51% are unlined. Unlined pits are usually a nightmare for both emptiers and property owners. For emptiers, there is little to no emptying that can be done for unlined pits. Emptying or onsite entrenchment of such facilities often lead to pits collapsing. For property owners, once unlined pits fill up, a new pit is dug up as a sanitation replacement. Relocating a property’s toilet within a limited plot size is a costly, inconvenient and challenging task. Moreover using unlined pits have serious environmental and health consequences due to, but not limited to the heightened potential for surface and groundwater contamination, leading to disease outbreaks.

In October 2019 and with the technical support of SNV, a research study was conducted in Kabwe to shed light into the question, ‘What would it take to help the Kabwe community manage their faecal sludge so that it does not stay within the direct living environment, and it does not become an environmental and public health risk.’

A total of 172 households across 20 of the 27 wards of Kabwe town were sampled for the study. As the sanitation facility is arguably one of the more pertinent components of the sanitation service chain, part of the study examined the durability of facilities, and explored household interest to invest in facility upgrade.

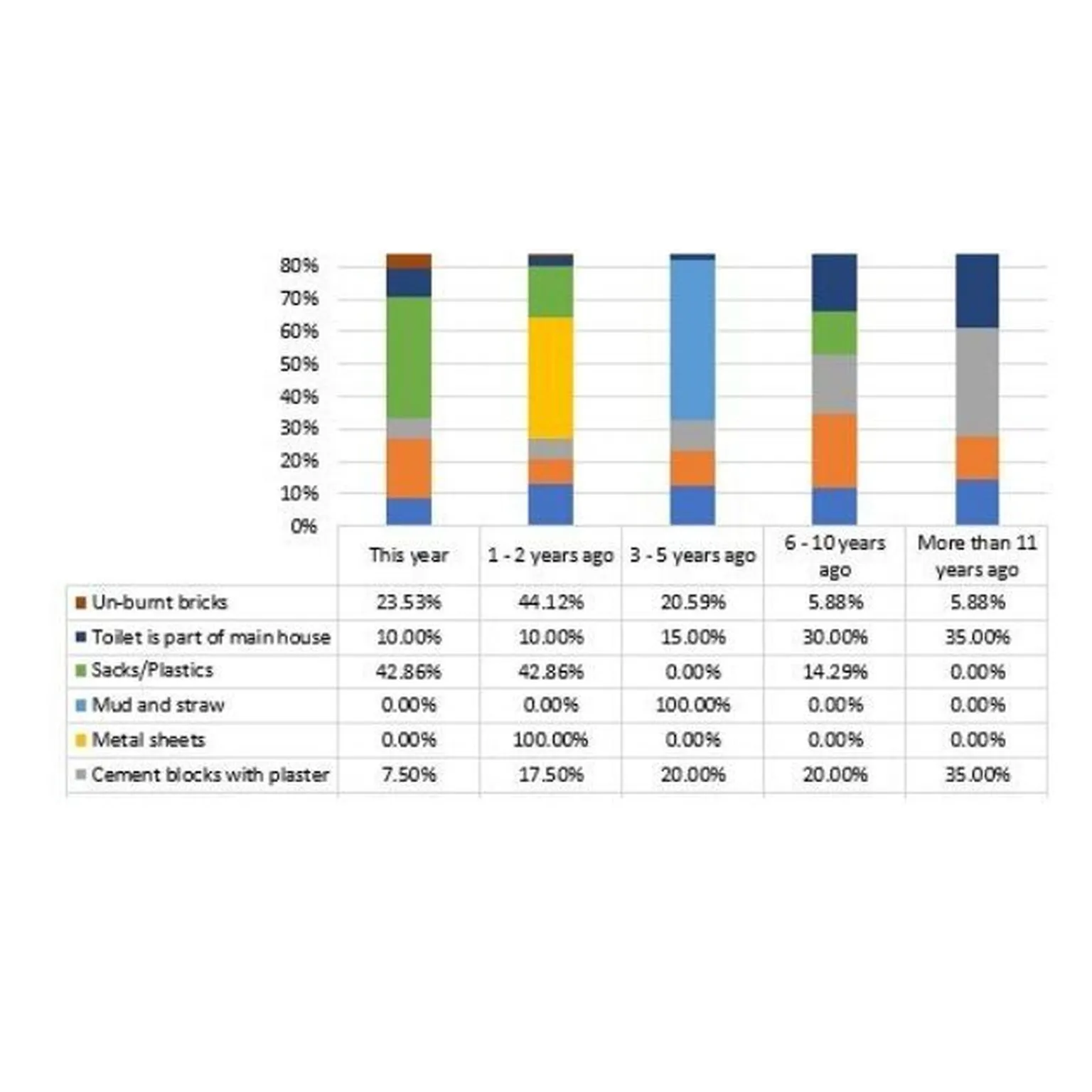

Chart of superstructure durability based on materials used

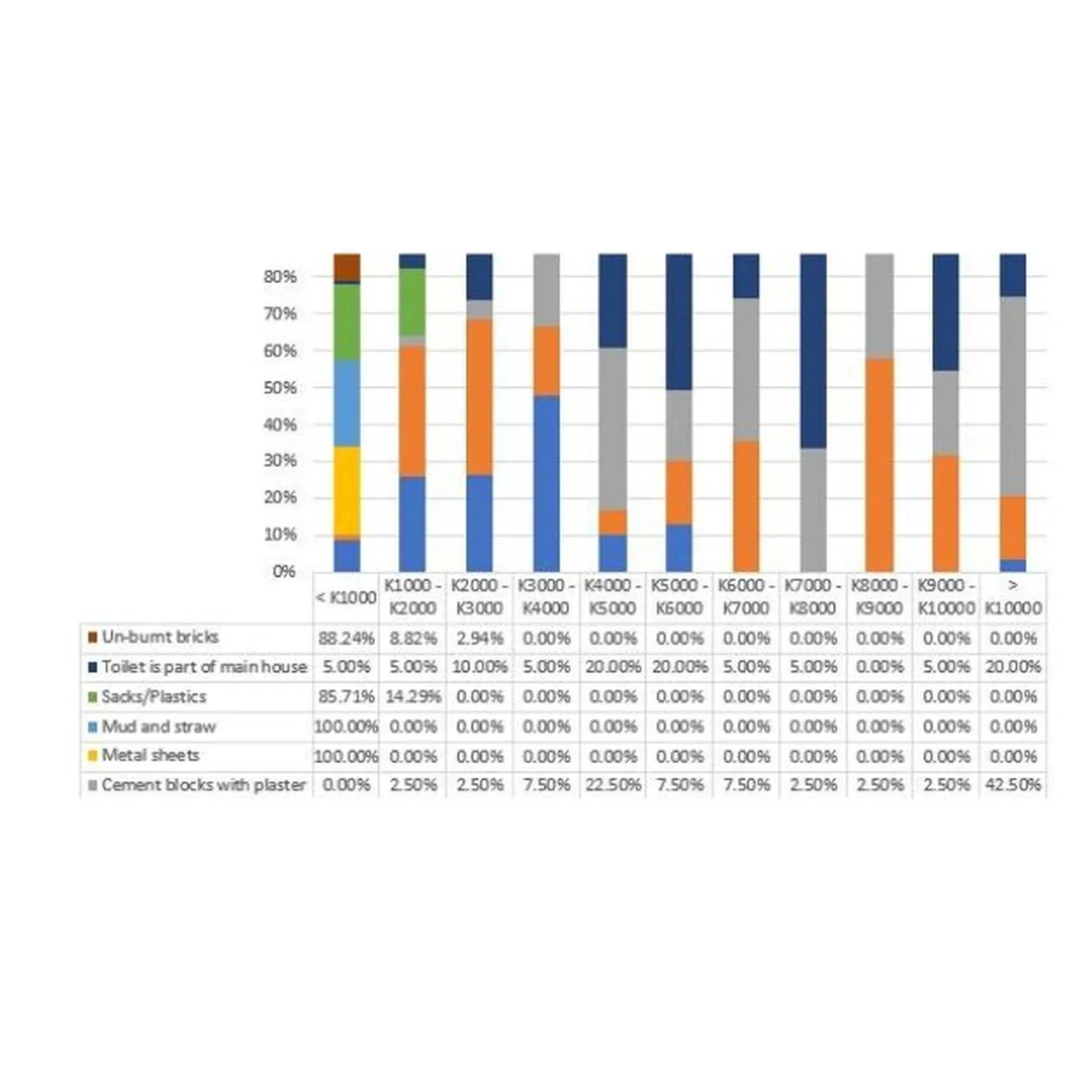

Chart of willingness to pay for improved superstructures in relation to chosen materials

Comparing lifespan of superstructures by construction materials used

A sanitation facility is made up of sub- and superstructures. Toilet superstructures provide shelter for the privacy and security of a toilet user. Substructures are where excreta is contained and where the process of excreta stabilisation commences; before emptying and further treatment. Without a toilet facility, there can be no proper faecal sludge management service.

A typical unlined pit latrine in Kabwe will have a superstructure built of unburnt bricks. In comparison, superstructures of improved toilets use burnt bricks, have a cleanable slab and a ventilation pipe to reduce odours.

In comparing superstructure durability based on materials used, those constructed with cement blocks fared relatively better than facilities that used other construction materials; regardless of the facility’s age. The durability of facilities made from cement blocks improved further when they were plastered: 7.5% (one year), 17.5% (1-2 years), 40% (3-10 years) and 35% beyond 11 years. Burnt bricks were also found to be durable, though the peak age of 61% of these superstructures was reached anywhere between one and five years.

In stark contrast to the positive performance of cement blocks and burnt bricks, more than 68% facilities constructed of unburnt bricks lasted for up to two years. Similarly, 85% of facilities made from sack material or plastic did not make it beyond two years. Those that used metal sheets lasted between one and two years. Beyond high levels of corrosion, metal sheets could easily be stolen and re-sold; a modus operandi shared by many respondents.

Understanding Kabwe households’ willingness to pay for toilets

Of the 172 households sampled, 62% belonged in the ‘poor’ and ‘poorest’ categories. Many used unimproved sanitation facilities and 67% of them fell in the least financial bracket of less than K 1,000 (US$ 76).[2] Planned residential areas and new property developers constituted 38% of the sample and expressed willingness to pay for varied financial brackets ranging from K 4,000 (US$ 305) to K10, 000 (US$ 763) and above.

The majority of Kabwe households that used less durable construction materials for their facilities were not willing to invest more than K 1,000 (US$ 76) for an upgrade. For households with facilities inside their main house, the willingness to invest in a new or better facility was varied; 20% between K 1,000-K 3,000 (US$ 76-230), 45% between K 3000-K 6,000 (US$ 230-460), 15% between K 6,000-K 10,000 (US$ 460-763) and 20% were willing to invest beyond K10000 (+US$ 763).

Out of the total sample, 23% were cement block with plaster-constructed facilities and 43% of them were willing to invest more that K 10,000 (US$ 763) for a new toilet.

The Kabwe research study validated earlier findings of the Chambeshi-Lukanga Sanitation Project baseline report – also undertaken by SNV with partners – which found a clear relationship between wealth and access to sanitation.

A typical unlined pit in Kabwe

A lined toilet in Kabwe

Discussion and recommendations

The study’s findings suggest that households are likely to realise savings if they invest in more durable superstructures. Coupled with lining pit toilets – the usability of the sanitation facility is likely to last for at least 10 years. Considerable sensitisation efforts are therefore required for people to regard sanitation as a priority and basic need. Stakeholders should not just assess sanitation access based on the number of locations for ‘squatting.’ It is high time to discuss the consequences of not having a proper sanitation facility.

Some recommended actions to take, include:

Conduct a formative research to better understand why users gravitate to less durable materials (beyond affordability), and how barriers to the willingness to pay for better sanitation facilities may be overcome.

With local authorities, support toilet upgradation plans through the co-development and implementation of national legislation and local ordinances that promote adherence to public and environmental health.

Strengthen capacity of commercial water and sanitation utilities to introduce new and professional faecal sludge management services in cooperation with private sector or local entrepreneurs.

Encourage private sector to incorporate sanitation improvements for households, especially those in the low-wealth quintile category in unplanned settlements, in their corporate social responsibility goals.

Partner with local CSOs and media to systematically disseminate messages on the dangers of poor-quality toilet facilities.

Written by: Moffat Tembo/Urban Sanitation Engineer

Notes

[1] Source: SNV 2018 Baseline study – Chambeshi Lukanga Sanitation Project. This baseline study was conducted as part of SNV's WASH SDG programme, which applies SNV's Urban Sanitation and Hygiene for Health and Development (USHDD) approach.

[2] https://www.xe.com/currencycharts/; US$/ZMK = 13.1 (Oct 2019).