Jemma produces Ethiopia’s high-quality onion and potato seeds

Communities work together to produce Ethiopian seeds for better productivity and income.

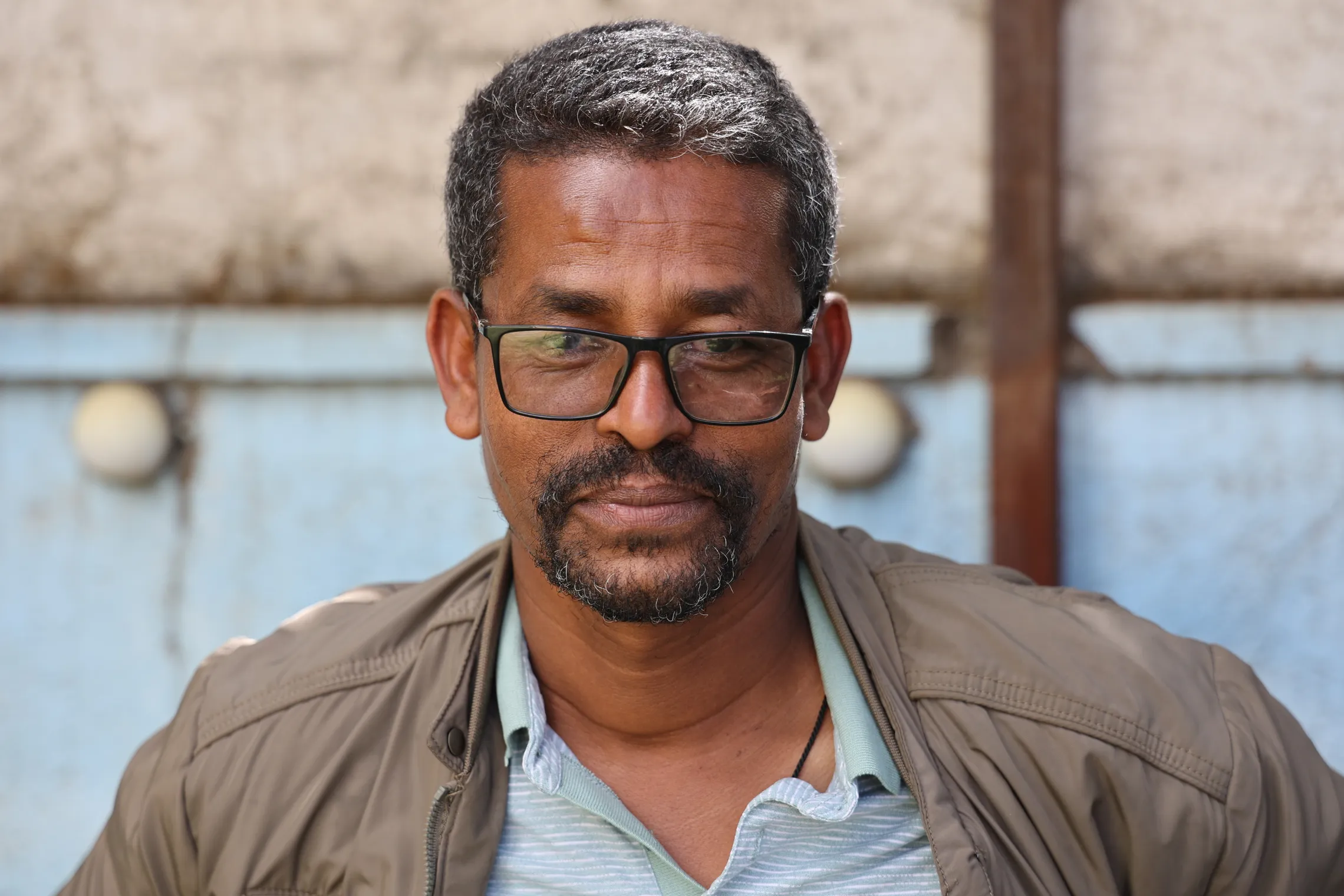

There are a few things that will fire up a discussion in East Africa as the seemingly innocent question of the origin of the Nile. But here, skirting the edge of Desalegn Tadele’s land, is the river Jamma, pronounced Jemma in Ethiopia. The Jemma then feeds the Abbay, a tributary that supplies 85% of the Blue Niles water. Mr Desalegn Tadele is proud of this, to say the least. His enthusiasm on the subject is also one of the first signs that Mr Desalegn is something more than a gently spoken university lecturer. After 18 years of teaching, he left to start his own business and, somewhat unsurprisingly, he named it Jemma Agrotech.

As Desalegn explains: ‘There was no organization or company that provided seeds. It was just the farmers, but their sources were not known, and the seed quality was very poor.’ This left a gap for Jemma, which Desalegn acknowledges. ‘Of course, there are imported seeds. These were of good quality but there we see again the problem of hard currency.’ Fluctuations in the dollar, Birr exchange rate, alongside strict governmental controls make the official exchange of currency a major obstacle in Ethiopia.

This means the availability of improved vegetable seeds in the Ethiopian market is less than 2% of the total demand. Desalegn describes how: ‘We saw it as a great opportunity. But it is a high-risk business. Competition from the informal sector can be high. Farmers are producing seeds, but with little understanding of markets. For example, we often see that some years we have a surplus and in others a scarcity.’ His interest and future success would stem from his years of experience in plant science that had primed him for the quality seed business.

We saw it as a great opportunity. But it is a high-risk business. Competition from the informal sector can be high.

Red onion was the perfect product to begin with. A visit to any market shows that it is produced on a very large scale in Ethiopia. Yet, the productivity of farms is generally low. This is mainly attributable to the poor-quality seeds they are using. This, together with the limited involvement of the private and public sectors in producing certified seeds, exacerbates poor production levels.

Jemma Agrotech was established to change this dynamic and provide quality, certified red onion seeds at an affordable price to smallholder farmers. In doing so the company is at once able to increase farmers’ access to quality seeds: increasing their productivity and income, and then, via contractual farming models, use farmer cooperatives and input suppliers as a channel for the distribution of the seeds they multiply.

Production in volume would be the first hurdle Desalegn would face. ‘Land is very scarce, especially irrigated land. We have to involve farmers, their land and their access to water.’ His own farm at only 5 hectares is nowhere near enough to scale production. He explains: ‘There is this big market, but we had limited land and we could only produce one crop a year, we also needed to rotate crops to keep the soil in good condition.’

There was a solution, but Desalegn knew it would take considerable funding. Asked why he did not simply approach a bank for a loan. His tone becomes one of quiet amusement: ‘The banks are not interested. They certainly are not interested in this [agricultural] sector. They see high risk. Banks support those with high capacity. The minimum they will support is 150 hectare investments. I only had 5 hectares.’

The banks are not interested. They certainly are not interested in this [agricultural] sector.

Desalegn knew that outgrowers were the solution, but also that this would take a big investment. ‘Without financial support, we could never increase our production capacity. I’d worked with outgrowers before but only 5 or 10. Once we received IAP support this became 60, and now we work with 120.’ Farmers were eager and readily made their land available.

Desalegn becomes more animated when discussing the role that challenge funds can play, saying: ‘Of course, they are very, very helpful. I had a plan; I knew the demand is so high, but I have limited capacity. The limited capacity comes firstly from finances, then there is the land. The outgrowers have the land but I cannot cover the advanced costs of those farmers.’ Obviously, without proof with which to convince potential outgrowers, Desalegn faced an uphill struggle to persuade them that not only was his plan viable but that it would be a far more profitable exercise for them.

Desalegn has provided each of us with 4 quintals of this new variety. Now, the leaves are looking better. The old one used to be smaller.

With IAP’s help Jemma went about marketing their plan and demonstrating the impact it would have on farmers crops. Two of his first outgrowers, Zenaw Andarge and Negussie Anbaw, take a break from tending their young red onion plants, and Zenaw tells us: ‘We used to plant seeds of the Bombay variety since it had adapted to this environment, but it was susceptible to disease.’ Since using the new Jemma variety, he describes improvements, both in their skills and in the plants’ quality. ‘Desalegn has provided each of us with 4 quintals of this new variety. He also provided us with training and agrochemicals. Now, the leaves are looking better. The old one used to be smaller; the colour of this one looks good.’ Negussie explains that before the Jemma seeds: 'When I used to plant on my own, they didn’t grow well, the plants were small.’

Regular income at a fair, above-market, price that these seeds can bring is just one factor that keeps the relationship between Desalegn and his farmers a strong one. As Zenaw says; ‘Retailing is not profitable for us, it’s just not as profitable if I sell to individual farmers. If we sell to Jemma, we know how much we will earn, and we can plan ahead and we will spend it well.’

Desalegn knows his farmers. They banter with each other. Discuss the crops and make jokes easily. He has clearly built a trusting relationship. This is reinforced by Zenaw’s comments: ‘Trustworthiness is key to a long-term partnership. If you tell me it’s one quintal or a quarter quintal, I will believe you. So, we need to trust each other. After harvesting and threshing, it’s very convenient for me to collect payment from one supplier. So, I only sell to Jemma.’

It is not just the 15% above-market rates that Desalegn pays the farmers. He provides training and the necessary access to markets that individual farmers are unable to develop. This has impressed the farmers. ‘Now, people come from Jemma to follow up on us and train us on how to spray pesticides. They have also linked us to the market. They pay a good price to buy our produce. So, we are very happy. We have no fears regarding market access.’ Negussie explains.

Now Desalegn is outsourcing seed replication to 160 outgrower farmers. He says that ‘For the last 3 or 4 years our company has produced 20 or 30 quintals; now we produce 60 or 70 (6000 or 7000 kilograms).’ Desalegn explains that: ‘More importantly is the risk to us to diversify the product. Because of IAPs intervention we are diversifying to potato production. We are doing this in the highlands where they grow potatoes.’

Zenaw believes that after seeing the positive benefits for him and his friends, more people will want to join the Jemma project. ‘We have experience working with the company and now there are families who will join us after seeing our achievements. Even today people are visiting to see the outgrowers at work. ‘There are many people that ask us to help them join. Anyone interested can do this. Even today there is someone who came to see what we do who is interested in joining. There are more people in other areas too. There is a lot of interest.’

Negussie explains that extended family members take part in weeding and tending the crop. ‘We all help each other, as it’s the culture of the community.’ They are often busy enough that they need to employ people from outside of the community. Negussie continues, explaining that when they are busy: ‘We can’t do it alone; we work through communal labour. When we don’t have enough family labour, we hire workers.’ This means additional labour, and the additional income for families takes Desalegn’s figures way beyond his 160 official outgrowers. And as Zenaw says; ‘We want farmers to access the seeds. We will be happy if they cultivate the seeds. We want everyone to benefit.’