Digging deeper: baseline insights to strengthen gender and social inclusion in rural WASH programming

Ensuring that potentially disadvantaged people have the voice, influence, and leadership roles in decision-making spaces is critical to achieve government goals for universal access to water and sanitation.

In 2019, SNV’s WASH teams in Nepal, Bhutan and Lao PDR conducted baseline surveys as part of its multi-country Beyond the Finish Line Programme. The teams applied SNV’s performance monitoring guidelines using a range of data gathering methods, such as surveys for households, health care facilities and schools, Focus Group Discussions with women and men with disability, and representatives from low-economic and low-caste/minority groups. Capacity assessments of line agencies using self-guided assessments and score-card systems were also conducted. Survey data were disaggregated by district, gender of household head, household with disability, and by wealth quintiles.

The GESI baseline studies build on foundational gender and social inclusion analysis undertaken during the multi-country programme's design phase and a series of formative research studies in the countries – including the last mile, disability and women’s leadership. Combined, these present a wealth of information to guide programming responses. Valuing the importance of gathered data and the need to translate these into strategies, the teams undertook a ‘deep dive’ to identify context specific insights and risks from a do no harm perspective.

Examples of commonalities across contexts

Wealth, age and gender influence perceptions of participation in community training and meetings relating to WASH. For example, in Lao PDR, though men in the ‘poorest’ wealth quintile had high attendance rates, they were reticent to speak. Elderly women were found to be more outspoken than younger women, but both felt that they had no influence over the outcomes of meetings. Interestingly, poor men and men with a disability were less likely to speak out in community meetings; in comparison to their women counterparts.

Local government capacity to mainstream GESI in services is limited. Areas to strengthen include using disaggregated data to inform budgeting and resource distribution, engaging with rights holder groups (e.g., Disabled People’s Organisations), or developing, implementing and accountability reporting on various social support mechanisms. Across all contexts, local government capacity scored the lowest in SNV’s performance monitoring indicators at the outcome level.

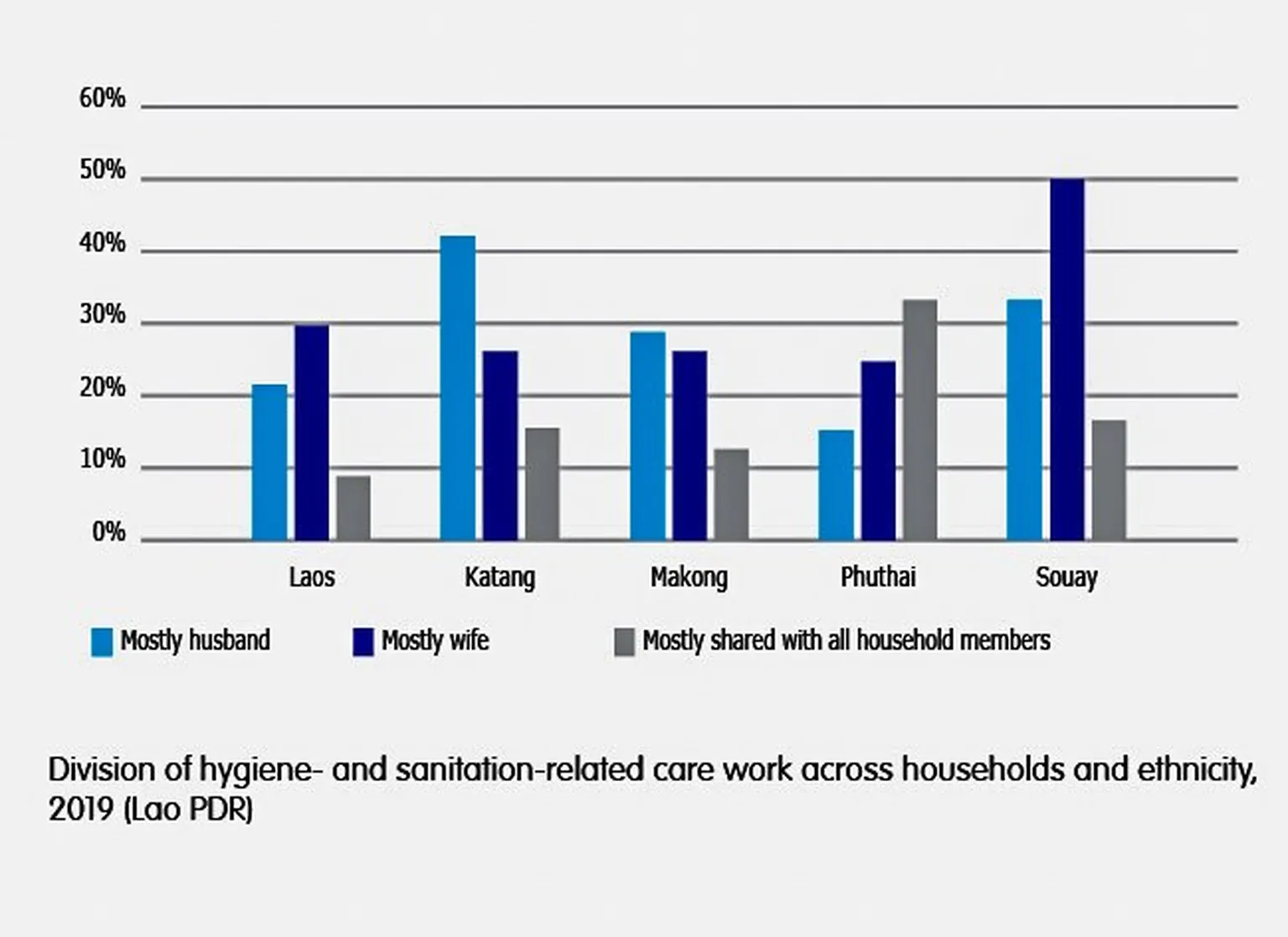

Men, as women, promote better sanitation and hygiene in their household while caring for children or elderly. However, income plays an important role in how care work is distributed. Overall baseline results suggest that women’s care roles are less flexible than men’s; i.e., women are less able to redistribute care work when household incomes increase.

Poorer households bear the brunt of sub-standard or no WASH services. In Bhutan, the country is witnessing a growing sanitation gap between richer and poorer households, which in turn, is intensifying health, economic and social challenges for people already at risk. In Nepal, households in focus districts from poorer wealth quintiles continue to travel longer distances to gather water – often from sources that provided sub-standard services. None of the poorer households benefitted from safe drinking water; compared to 22% of the richest households. Often, investments in water treatment at points of use fell on the poorest households.

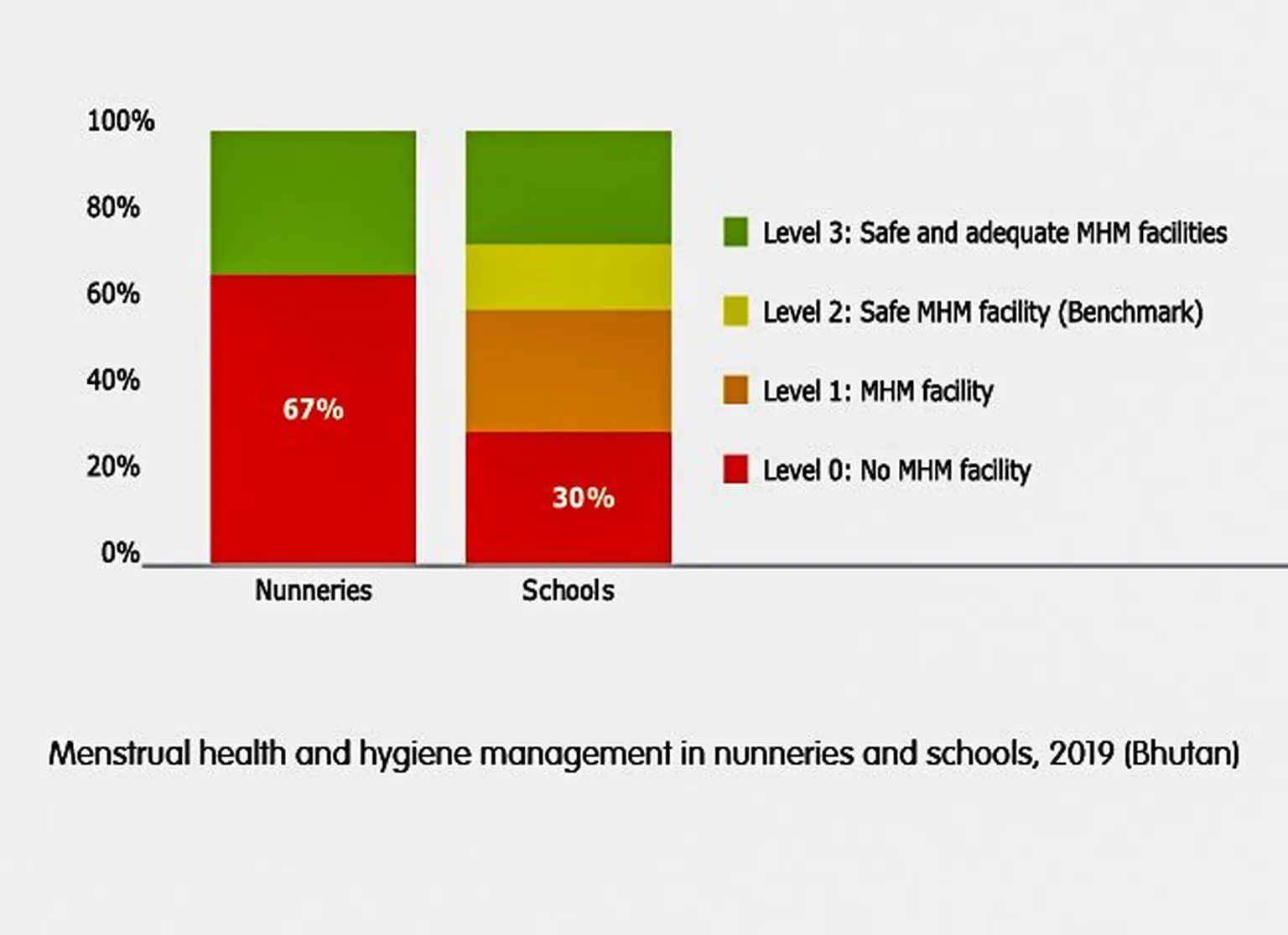

Toilets and menstrual hygiene facilities in schools, religious institutions and basic health centres are limited and typically not accessible. Limited to no presence of menstrual health and hygiene (MHH) services impacts on girl’s school attendance, safety, comfort, dignity and human rights. Whilst some adjustments had been made to promote the accessibility of toilets in health care centres, these did not follow national accessibility standards.

Challenging assumptions

Ethnicity limits or expands opportunities for women to take leadership roles and influences division of household (care) labour in WASH. In Lao PDR for example, men in some ethnic groups had a greater share in care labour, in others it was balanced; interesting findings that counter the dominant assumption that it is the belief that women and girls play this role for the household.

Approaches to generating demand (‘triggering campaigns’) for sanitation can reinforce inequitable care arrangements and redistribution. For example, many outreach strategies to trigger demand in WASH focus simply on one representative per household (thereby seeing the household as one unit, with one person who can fully represent everybody's needs and perspectives). Many behaviour change campaigns have also overlooked men as care givers.

Ways forward: ‘do no harm’

Going forward, insights from our baseline surveys validate the need for WASH programming to interact with approaches that Do No Harm as a strategy to, for example,

increase awareness of and attention in redressing hierarchy and power in household and community participation and decision-making to reduce the risk of delivering to the needs and interests of specific or a small segment in societies.

strengthen government capacity to design, implement, monitor and be accountable for evidence-based and targeted WASH programmes to enable duty bearers to bridge growing water or sanitation gap between richer and poorer households. Inclusive WASH governance systems are likely to lead to health, economic and social benefits – not only for potentially disadvantaged people, but for entire populations.

identify and work with people with disabilities – and their households – through the development of respectful engagement approaches and methods in decision-making or designing WASH interventions. To prevent harm for example, recognising that people with disabilities may experience different forms of violence, e.g., emotional violence (relating to issues of shame, burden placed on care givers, etc.) and neglect (in the case of people who are dependent on the support of others to access water, sanitation and hygiene).

Banner photo: Woman mason in Dagana Bhutan (SNV/Aidan Dockery)

Notes: The Beyond the FInish Line programme builds on SNV's long-term presence in and partnership with the WASH sectors of Bhutan, Lao PDR and Nepal. Visit the SSH4A in Bhutan, SSH4A in Lao PDR, and Inclusive and sustainable rural water supply services in Nepal project pages for more information. | More information on the Australian Government's Water for Women Fund may be viewed here.