Urban Sanitation in Bangladesh - Component 3: Governance, regulations and enforcement

Once the laws are in place, compliance becomes key.

The government is the duty bearer when it comes to ensuring safe sanitation for its citizens. And more than anyone else, local government is key to effectively implement this sanitation.

Together with SNV, the city of Khulna and the towns of Kushtia and Jhenaidah have set up the supply of safe and affordable sanitation services (component 2). But their role doesn’t end here.

Establishing rules, regulations and responsibilities is key to ensuring that safe sanitation becomes a reality. In this part of the world, policies, rules and regulations are generally available, but their enforcement is too weak.To be able to fulfil their public duties, authorities must ensure compliance with regulations and impose taxes (and/or a fee) to cover the costs of services.

Figure 1 official launching of the Institutional and Regulatory Framework (IRF)

SNV has contributed towards developing a new Institutional and Regulatory framework (IRF) for safe sanitation in Bangladesh. Our field experiences generated bottom up evidence for developing this IRF. The current IRF for faecal sludge management in Bangladesh identifies ways of implementing services, and defines the roles and responsibilities of institutions and stakeholders. We are now providing crucial advice on the development of by-laws, including guidelines, tools and procedures to make the IRF operational at city level.

3.1 Enforcement of national building codes for sanitation facilities.

Don’t allow the problem to worsen with the expansion of the city.

The first step in the sanitation chain is the toilet itself. Safe containment of sludge and prevention of uncontrolled overflowing of waste is essential. As the problem largely flows unseen (and people’s only direct wish is to get their debris out of their backyard), rules and regulations are essential for public health and safety. Rules for approving building plans for new houses and septic tanks do exist, but due to weak governance and insufficient resources of the authorities, these rules have never been seriously applied. As a result, new buildings lack well-functioning septic tanks, also because many of them are constructed by masons without any technical expertise whatsoever. In addition, there is a lack of willingness and human resources from the government authorities to inspect toilet facilities, once built.

This needed to change, we must ensure that quality septic tanks are installed in new buildings, and together with the city authorities we did just that. It is now mandatory to submit the full drawings of sanitary systems (including septic tanks) when applying for a building permit. In addition, approval from the appointed authorities is required after construction of the building (up to the plinth level), to ensure reality matches the building plans.

SNV and the city authorities are developing a workflow to approve building plans. We are writing guidelines, checklists, and verifications for the design and construction of sanitation facilities. We will also organise follow-up procedures and monitoring of progress after buildings are constructed up to the plinth level. Outsourcing the verification of the septic tank designs by an architect or engineer, with the owner paying for these services, is currently a matter of discussion.

Last but not least, the Khulna Development Authority is guiding local designers, engineers and construction companies on national building codes and approval workflows.

Safe sanitation in new buildings will put a stop to a growing problem, but the major challenge is the upgrading of existing latrines and the containment of their waste. At this moment most houses do not comply with the building code. In response to this, SNV initiated an action research to find out the necessary improvements. These improvements turn out to be both necessary and feasible; inlets and outlets of septic tanks can be repaired for example, and tanks can be compartmentalised. Based on these findings, we have designed an orientation program for masons and supervisors. However, people are reluctant to upgrade their current facilities since there is no incentive or enforcement for them to do so. Moreover, the sewer utility has initiated a sewage master plan and people expect the sewage line to arrive at their premises in the foreseeable future. Considering the required resources for such an investment, we are not that optimistic. We are therefore discussing necessary measures with the city authorities.

An interesting paper on these developments: Exploring Smart Enforcement

3.2. Tax introduction

Current fees for services only cover operational costs for emptying of waste. We need additional revenues to cover the costs for improvement and expansion of these services.

In 2014, Bangladesh released “The National Strategy for Water Supply and Sanitation”. This strategy provides specific directions to address faecal sludge-related issues. One of the prime objectives is to prevent huge upfront investments by assuring gradual full cost recovery, including costs of capital, operation, and maintenance. Only safe sanitation that “pays-as-it-grows” is a sustainable path to expansion.

That same year 2014, the Local Government Division included a Sanitation Tax in the Paurashava Model Tax Schedule. Paurashavas are the municipalities of smaller towns. Any Paurashava can collect up to 12% of holding (which is property- land and building) tax for providing sanitation services.

The Jhenaidah Paurashava was eager to introduce the Sanitation Tax, enabling them to expand their services and maintain their infrastructures in a sustainable manner. SNV provided technical support; reviewing legal provisions for introducing a sanitation tax, proposing different alternative models for taxing and rating based on the available data, and lastly we prepared an action plan with implementation guidelines for the introduction of this new tax.

The city council decided to charge a 5% tax for sanitation services on top of the existing fee for desludging. This fee per use only covers the operational expenses for emptying a septic tank. The extra tax revenue will be deposited in a separate account, and only be used for the expansion of sanitation infrastructure and the strengthening of sanitation services.

Jhenaidah was the first town in Bangladesh, South Asia even, to introduce a sanitation tax. Can you imagine? No one has imposed such a tax until Jehenaidah decided to be a frontrunner. Such pro-activeness is not without its risks, because imposing taxes doesn’t immediately make you a popular election candidate.

However, based on the positive tax experiences in the town of Jhenaidah, the large city of Khulna is now considering the introduction of this scheme as well.

3.3 Integrated Municipal Information System

Have you emptied your septic tank this year? One second, let me check…

Sanitation can only be real safe when compliance is city wide. Safe buildings, sufficient taxes, and regular desludging are essential elements. Here, like everywhere, detailed information is key. That is why SNV has set up an online Municipal Information System.

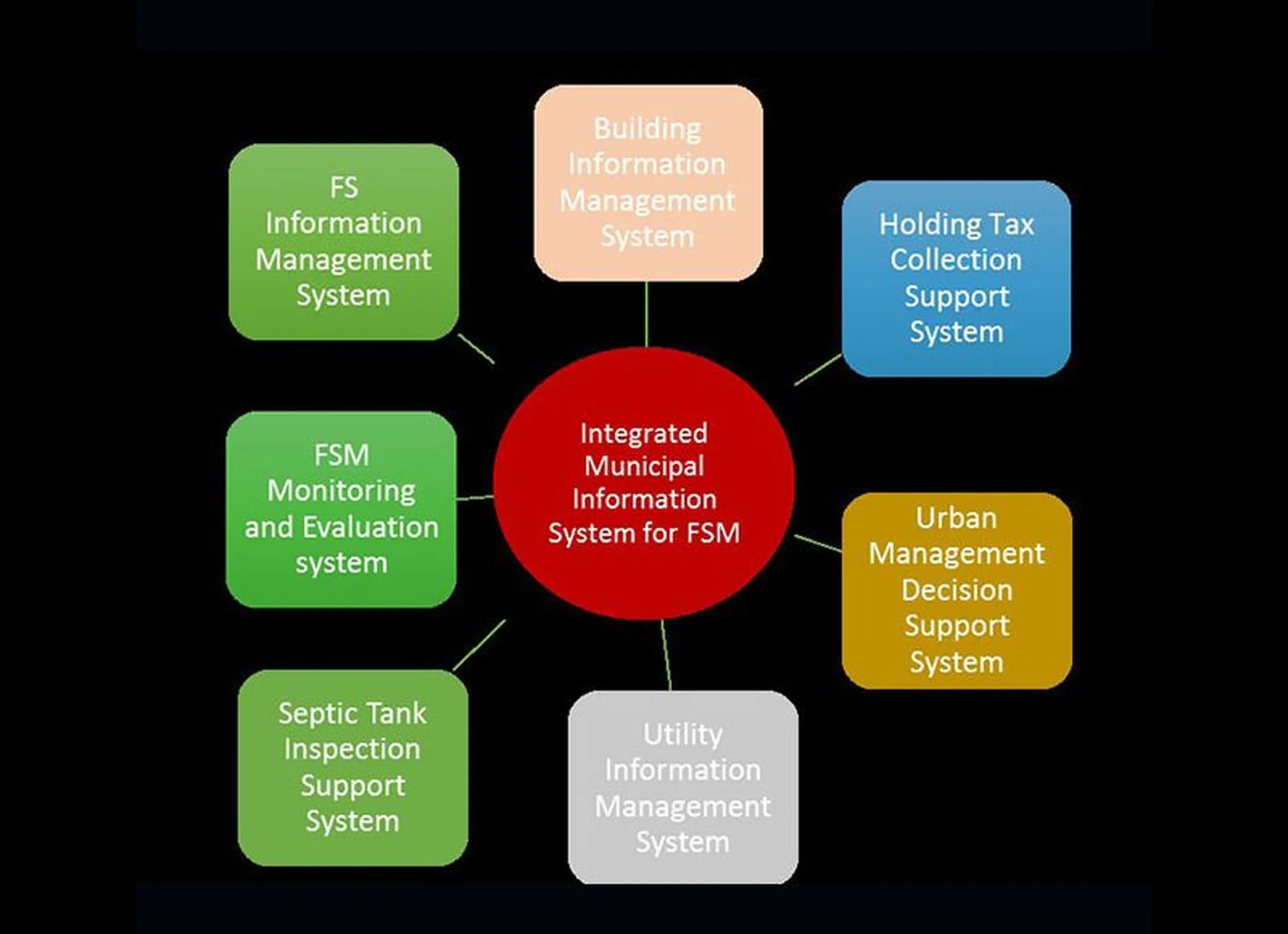

Below you can see an overview of modules (information buckets) in the Municipal Information System.

Urban Sanitation in Bangladesh - Component 3: Governance, regulations and enforcement

Let’s give a bit of background again. The population of Khulna, Kushtia and Jhenaidah is growing rapidly. The areas covered by the city expand in an unplanned way. Slums are densely populated, and all this turns municipal governance into a mind blowing challenge. Especially if you realise that until this very day, many of the city councils still work with pen and paper, resulting in slow and tedious processes. There is a lack of information to support overview, planning and decision making. Fortunately, information technology develops at an accelerating pace as well. For some years now, the concept of SMART cities has been raising expectations worldwide; intelligent street lights, intelligent garbage collection etcetera. But the best results might be gained by implementing smart city concepts in the busy and chaotic metropoles of developing countries.

You may know the story about the streetlights in London. London was the first city with gas lit streetlights, but this head start inhibited them when electricity came into play. ‘Newcomers’ implemented electrical streetlights first. Likewise, Bangladesh may soon leapfrog into state of the art 21 century information technology.

SNV developed the Integrated Municipal Information System (IMIS) to enable the local authorities in Khulna and Jhenaidah to have information at their fingertips. IMIS is powered by a Geographical Information System (GIS), which is an online tool allowing you to combine information layers about spatial objects. GIS is used worldwide and turns out to be a useful tool for mapping the exact location of septic tanks. The Municipal Information System (IMIS) also contains city-level data such as: administrative boundaries; municipal infrastructure (roads, drainage networks); city land use; slum locations; the location of buildings and their structure, septic tanks plus desludging frequency; household tax data; a list of certified pit emptiers; enlisted masons; etcetera. The visual tooling of IMIS enables users to quickly analyse all data sets. The objective of the tool is to support efficient planning, policy decisions, a smooth service delivery, and real time monitoring of municipal desludging services.

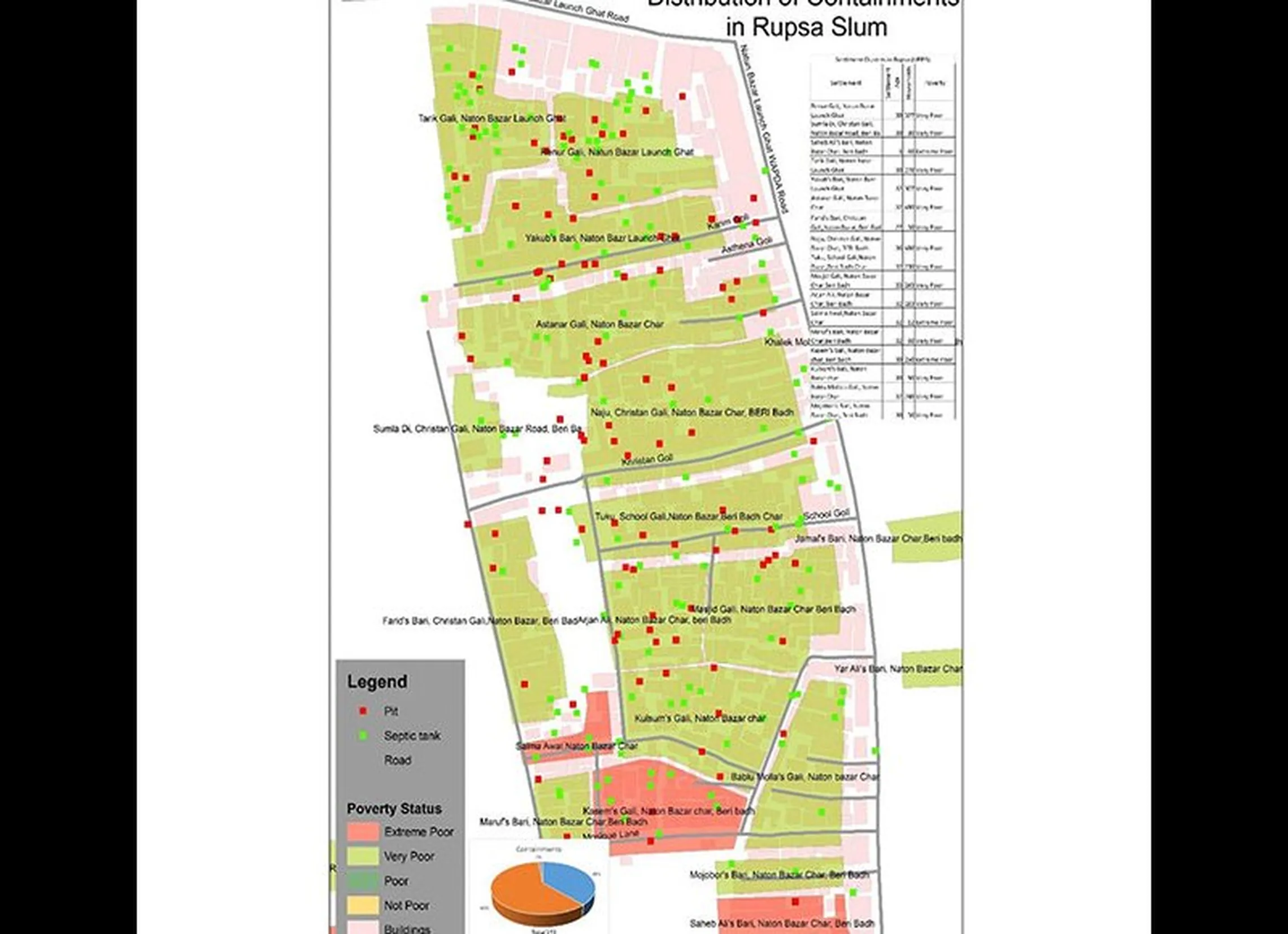

Below, you can see an example of a visual overview of data derived from the system, such as location of pits and septic tanks in a slum, combined with wealth indications on sub slum level - not surprisingly consisting of very and extremely poor people. The pie chart shows that 60% of houses have a septic tanks, 38% a pit, and 2% nothing at all.

Urban Sanitation in Bangladesh - Component 3: Governance, regulations and enforcement

By the way, this is what very and extremely poor looks like. An alleyway and a public toilet for 25 families.

Urban Sanitation in Bangladesh - Component 3: Governance, regulations and enforcement

Urban Sanitation in Bangladesh - Component 3: Governance, regulations and enforcement

What’s next?

We have updated you about consumer behaviour change and demand creation, the business model for safe & affordable services, governance, regulations and enforcement. It is now left with the part that usually gets most attention because it is so visible; component 4, the process of treatment, disposal and re-use of sludge. But SNV didn’t start with a faecal sludge management treatment plant, to watch it lying idle and deteriorate for lack of customers. In this learning project we have turned things upside down. We wanted to know about urban consumers first, about their situation and their needs. We went further and asked - can we build a business model that generates enough money for shit to sustain itself? The answer is yes. Then we dug deeper to motivate and share knowledge with the government. Ultimately the plant was set up to meet demand.

Seems like the boxes of citywide sanitation are ticked. Next up – the faecal sludge management treatment plant. Coming soon.