Urban Sanitation in Bangladesh - Component 2: Safe and affordable sanitation services

Component 2: Safe and affordable sanitation services

We set up a safe desludging service from pit to treatment plant without huge upfront investments, and knowing that customers are willing to pay a fee that covers all operational costs.

We developed an end to end desludging service with a call centre, a household database, safe mechanical emptying, transport and a treatment facility (see component 4) - proving that a sustainable business model in faecal sludge management (FSM) is feasible. With this proof that ‘there is money in this business’, we are now raising the interest of the private sector to scale up capacity.

2.1 Business models

“There is money in this business, and if we can make that clear, nobody will care that it comes from shit.”

In general, the interest of the private sector to invest in sanitation services has been low, mainly because the necessary start-up capital seems high while market demand is low. Next to investigating consumer perception and raising demand (see component 1), we have developed a viable business model to show government and the private sector that desludging does not need to be making a loss. We can prove that there is money in shit.

The ‘willingness to pay’ study identified that consumers were prepared to pay up to approximately 1,000 BDT (10 Euros), which allowed for a break even service. After that, we focused on showing that safe desludging can be scaled up to a citywide service, step by step, without the huge upfront planning and investments required for sewerage as single solution.

Manual emptying is still predominant but beside that Local Government Institutions (City Corporation and Municipality) and Community Development Committees are also providing mechanical emptying services. The Khulna City Corporation (KCC) charges BDT 2,850 (29 Euros) per trip (5,000 litres) for the mechanical emptying of faecal sludge, and has a prescribed format and procedure to receive the service which requires at least 3/4 day notice. As the actual Vacutug used for emptying sludge is large and inaccessible by 45% of households in Khulna (due to narrow roads), the pit latrine users do not prefer to use this service. Currently, KCC vacutugs are mainly serving households and institutional clients (offices, hotels etc.) with a septic tank. KCC has agreed to outsource FSM services and is currently finalising terms and conditions for the contract. KCC service process was revisited and simplified and now the service is available within 2 days from application, depending on the queue.

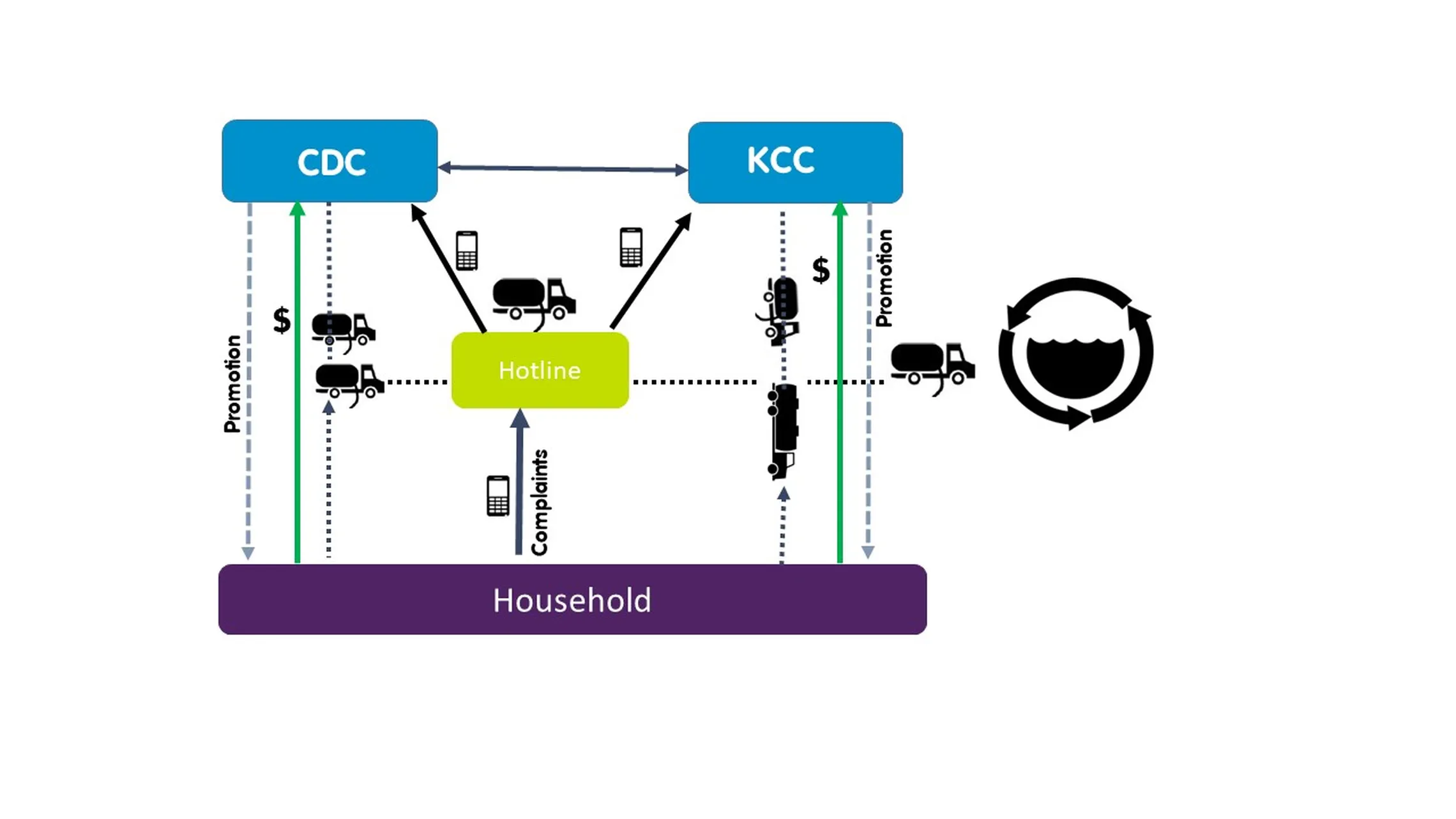

Another service provider is the Community Development Organisation (CDC), which charges BDT 1,000 (10 Euros) per trip (1,000 litre), which is expensive in terms of per litre cost. As the CDC vacutug is a smaller vehicle, and it can be accessed by 73% of the households including those situated on narrow roads and streets (8ft wide). Only three CDC vacutugs were operated by 3 cluster CDCs (ward level committees), and so it was difficult for customers to track the vacutug in Khulna. After a series of discussions with CDC members, a CDC federation manager now manages all three vacutugs, and an extra charge is levied if a manual emptier has to clean additional hard sludge accumulated at the bottom of the containment.

Business Model in Khulna involving both CDC and KCC

2.2 Occupational Safety and Health

Today’s reality is that pits are still emptied bare handed by manual emptiers, and we have to start working from there.

Whereas the end goal is a mechanical process of emptying containments (septic tnaks and pit latrines), the reality is that the overwhelming majority of containments are still emptied manually, bucket by bucket. Investments in mechanical devices have not materialized rapidly, so, manual emptying will not disappear in the near future. Because occupational safety is the responsibility of employers and their service model, working towards safe working conditions for emptiers is a stepping stone to improved service delivery.

To minimise accidents and ensure the health of manual emptiers, SNV has played a vital role in mainstreaming Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) measures in sludge collection, transportation, disposal, processing and re-use.

SNV developed new OSH guidelines, and training manuals, including a section on Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). A list of emptiers in all the 3 towns were collected and validated by city authorities, and 141 out of 200 endorsed emptiers were trained. A draft certification procedure to increase compliance was prepared, and discussion is ongoing with National Skill Development Council (NSDC), with the eventual goal of the guide becoming mandatory. Local Government Division has proactively stepped in and distributed a Circular to all Local Government Institutions to initiate enlisting of all emptiers, and to ensure occupational safety and health of emptiers. The Department of Public Health Engineering has been requested to develop a training manual on OSH. In addition, a health insurance scheme for emptiers is also under development allowing emptiers to claim medical costs for injuries occurred during working hours.

Read more : City cleaners, stories of those left behind

2.3 Emptiers to Entrepreneurs

From a shitty job to a decent business - growing out of manual labour.

Our mid-term aim is that emptiers of pits (or masons that build latrines) can buy mechanical devices, and grow into professional SME entrepreneurs. However, to be able to establish an enterprise, these workers will need rigorous capacity building and some seed capital.

During this project, 30 emptiers were selected from three towns to participate in an Entrepreneurship Training where basics knowledge about starting a business was discussed. Based on performance during the training, 10 emptiers underwent business plan development working sessions with Enterprise Development Experts. The experts will continue to provide technical backstop during their initial stage of business.

A seed fund provides solutions for the lack of institutional support from local authorities and institutional credits to fund short and long term financial needs of emptiers and the sanitation sector. Seed Capital has already been rolled out and 6 local entrepreneurs have been provided with a loan (BDT 50,000-BDT100,000 or 500-1,000 euros) to establish enterprise like manufacturing of ring slabs for pit latrines, or for buying a motorised tricycle along with barrels for transportation of sludge to transfer stations. The Federation of CDC is the Fund Manager wherein KCC is providing necessary support to make the operation effective and transparent.

2.4 Private sector involvement

In order to cover city-wide mechanical emptying services, additional service providers are needed as demand rises. After the business model was established, SNV and the Local Authorities (Khulna City Corporation, Jhenaidah Municipality and Kushtia Municipality) agreed to explore outsourcing possibilities for FSM.

We therefore decided to try and engage the private sector. The city authorities of Khulna want to outsource the management of the FSM service to private enterprises with the right expertise. Developments include the following: The Khulna City Council has already approved this outsourcing process, whereas Kushtia Municipality has already outsourced the operation and maintenance of treatment plant including compost facility to an established Organic fertiliser company. In Jhenaidah the Municipality has outsourced the entire FSM services to a local NGO. One of the major challenges is to increase the demand for emptying. We also have to realize that until now, sludge emptying has always been left to people who live at the fringes of society, with little engagement from the private sector.

A few years ago the Kushtia Faecal Sludge Treatment plant (FSTP) was not operating at full capacity, and its production of co-compost was negligent. But after outsourcing the operation and maintenance of FSTP to an enterprise producing and promoting organic fertilisers (Aprokashi), results have shown to be successful. The quality of co-compost coming from the plant has improved drastically, making it lucrative to sell; and ultimately adding another source of income to the business case of faecal sludge management.

2.5 Construction of mobile secondary transfer stations (mSTS):

One of the major challenges across the sector is to ensure the transportation of the sludge to a designated disposal site because of long distances to FSTP. Community members often do not care what happens once the sludge it sucked out from their premises, and city authority enforcement on this issue is also very weak. Furthermore, emptiers lack incentive and enforcement to desludge at designated disposal sites, due to the location of the sites being situated far away. Drivers of small vacutugs are discouraged from driving these distances given that their tanks can only hold a small amount of liquid, resulting in several back and forth commutes at a significant cost. This leads to most of the sludge being disposed in the nearby waterways or on marginal land, and in the process harming the livelihoods and health of the people.

In order to minimise frequent driving of smaller vacutugs, a truck with a container capacity of 7000 litres has been manufactured locally which works as a transfer station for smaller vactugus. This Mobile Secondary Transfer Station (mSTS), will provide an easier means for waste disposal at designated sites especially because it can additionally be used by households and accessible in narrow streets – typical in this setting.

Read more about Urban Sanitation in Bangladesh:

Read the Previous Chapter - Introduction

Read the Previous Chapter - Component 1

Read the Next Chapter - Component 3

Read the Next Chapter - Component 4