Urban Sanitation in Bangladesh - Component 1: Consumer behaviour change and demand creation

Consumers are unaware of the dangers of unsafe emptying and treatment of their faeces, yet they are willing to pay for safe services after they are informed about the risks. Our behaviour change campaign focuses on government regulations, annual pit latrine emptying, and improved sanitation services - just one phone call away.

The project started with a baseline study aimed to identify the current situation in Khulna, Kushtia and Jhenaidah. The results of this study laid a foundation for the Programme.

1.1 Baseline study:

People don’t know their pits need to be emptied regularly, and safe services are absent.

The baseline study focused on five impact indicators;

access to sanitary facilities,

hygienic use and maintenance of sanitation facilities,

access to handwashing with soap,

safety of pit emptying and conveyance, and

safe treatment and disposal.

Data were collected from households in all three cities, and then segmented based on an asset-based wealth-ranking method (Bangladesh 2011 Wealth Index Questionnaire developed by a DHS programme). All the households depend on onsite sanitation system (septic tank or pit latrine). The results of the baseline study showed that both access to a sanitary toilet and handwashing with soap, directly improve with an increase in wealth. However, the necessity of safe pit latrine emptying, and the treatment and disposal of faecal sludge is unknown to the population. Below are the major findings of the Baseline Survey.

The toilets

In general, excrement travels from the toilet to septic tank, to some sort of soak well or drainage pit which is used to soak up septic tank effluent into the surrounding soil. The good news in Bangladesh is that open defecation has become a rare phenomenon, because 99% of households have access to toilets nowadays, however households face many challenges around toilets and waste management. The majority of these toilets in Bangladesh have a septic tank (in Khulna - 61%), but, due to a lack of proper design and installation, no collection and treatment facilities, and facilities without a soak or drainage pit (84% in Khulna) – almost all faecal sludge ends up in surrounding waterbodies, which could result in serious health threats to people. Even though it is mandatory to have a septic tank with a soak well, soak wells do not function efficiently due to the high water tables. This amounts to 52% (Khulna) and 34% (Kushtia) of the total amount of households with a toilet!

In all three cities, about one-third of the toilets were functional and clean, but the lower two wealth quintiles face privacy issues with personal and communal toilets, such as the lack of intact walls, locks on the door, and running water in the toilet cubicles. These issues are especially important for women and pose risks for them! Additional common issues include no water seals (used to trap gases and prevent rodent or insect contact with faeces), blockages in the water seal, or unimproved toilets. Around 95% of households in all three cities clean their toilet by pour flushing (i.e.: pouring water from a bucket into a toilet bowl to flush excreta). The frequency of toilet cleaning is satisfactory, but many households, especially in Jhenaidah, do not clean their toilet on a daily or weekly basis.

Furthermore, 60% of the pit latrines in Kushtia are twin pit latrines without proper alternating connections between the pits and actual latrine. Twin pits are laid some distance apart, and while one pit is collecting waste, and the other is resting and degrading the materials, which are thereafter excavated safely and used as fertiliser. Poor connection between these two parts (usually connected by a Y-junction) indicates a lack of understanding of the concepts and benefits of proper twin-pit latrines and effective small scale faecal management in urban settings.

About a quarter of the households in Khulna City Corporation, Kushtia Municipality and Jhenaidah Municipality, do not have a specific handwashing facility, which can discourage members from washing their hands regularly and especially children if left unattended. This may be a result of decision making in home, as caretakers - who are mostly women - do not have a strong voice when household decisions are made about installation of handwashing facilities. .

Desludging

Almost all households in the three cities practise unsafe emptying of faecal sludge, irrespective of wealth. Although mechanical faecal emptying with a motorised pump (by Vacutug) and container mounted on a small vehicle was introduced a few years ago through a United Nations Development Programme project; this initiative is not functioning properly due to lack of proper public awareness of this city-run service. Besides, the procedures for mechanical emptying are far more tedious than just calling a manual emptier.

After waste has been collected in mobile containers, and transported, there are no properly functioning disposal sites. Most of the mechanically collected sludge is still dumped in undesignated areas - even though Kushtia and Jhenaidah have treatment plants in place.

The study made it very clear that having the physical infrastructure of a toilet is not enough for improving sanitation access in urban areas. Ensuring proper FSM requires a demand side approach, and marketing of these city-led waste removal services to the public is just as important, as well as installing a functioning latrine.

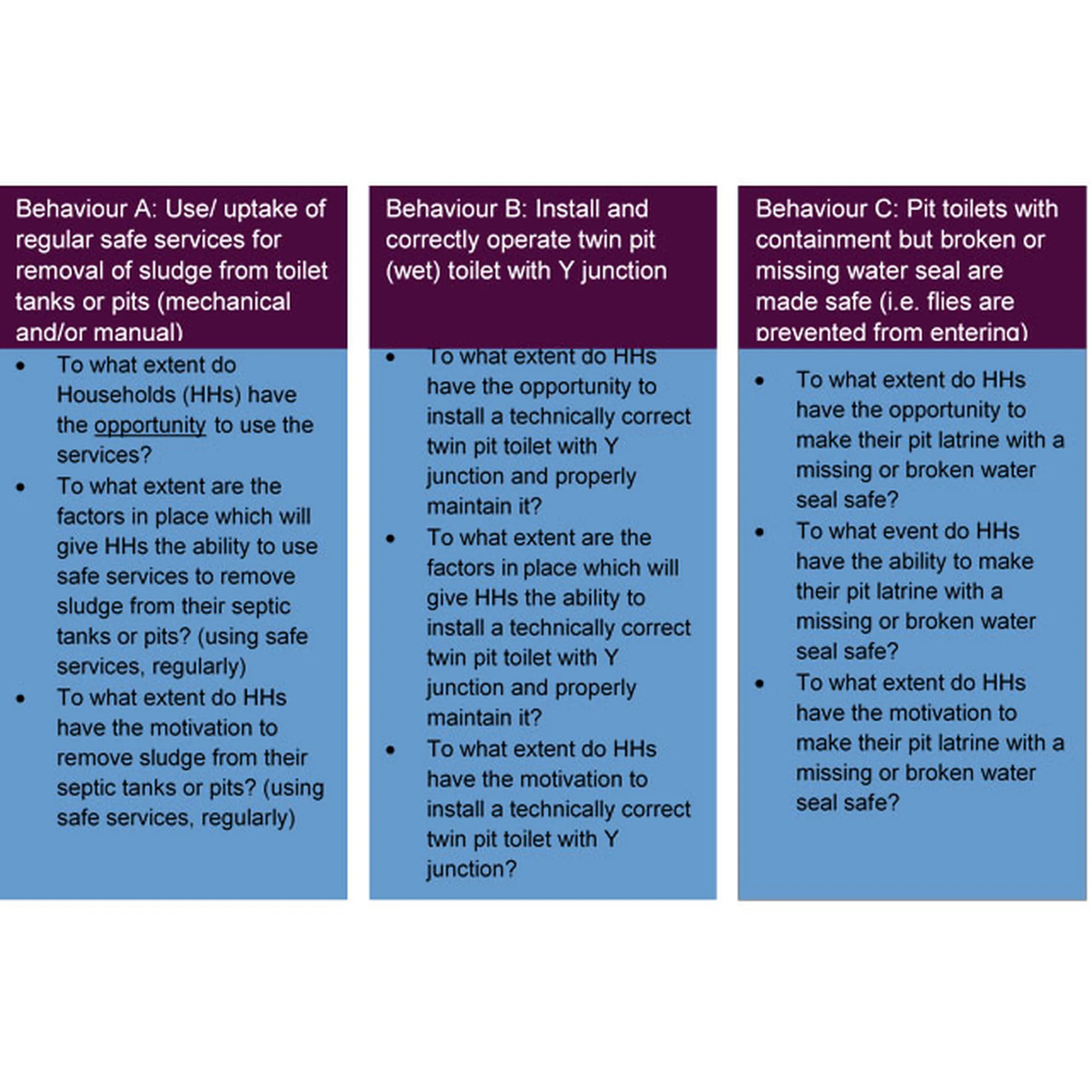

Based on the above findings, and a design workshop with relevant stakeholders, three behaviours were chosen for the formative study:

Use/uptake of regular safe services for the removal of sludge from toilet tanks or pits.

Install and correctly operate twin pit (wet) toilet with Y junction.

Pit Toilets with containment - broken or missing water seal - are made safe (i.e. flies and rodents are prevented from entering).

1.2 Formative research – Consumer Behaviour Studies:

People consider the emptying of pit latrines a low priority and a hassle. Only manual emptiers provide an easy service, and nobody considers their health and safety with this labour - which in some instances may take several days.

The objective of this research was to better understand the drivers and barriers of consumer behaviour change on the three issues of faecal sludge removal and functioning twin pit latrines. Evidence collected from this analysis would set the stage for effective behaviour change communication (BCC). The SaniFOAM [1] framework was used to identify key determinants that influence each behaviour.

Findings from the formative research were:

Pit emptying is a low priority expenditure for consumers.

Users tend to avoid the hassle of emptying their pits in time, and instead wait until they overflow, and when emptying becomes absolutely necessary (emergency emptying).

Users prioritise the following FSM service characteristics: available at short notice, at night, at low cost, easily organised, and fully emptied. Manual services are generally perceived to have these characteristics.

Manual services are preferred by most consumers because they are significantly cheaper and can be arranged easily and at short notice.

Users nor sweepers are concerned about the health and safety of manual emptying.

Respondents suggest that increased education and promotion of good sanitation could encourage people to practise better behaviours.

Faecal sludge is thrown in drains, rivers, canals, or in open spaces because it’s quick and convenient.

Respondents suggest that laws related to sanitation are not enforced, with inspectors currently turning a blind eye to the dumping of faecal sludge.

Mechanical emptying services at affordable rates were successful in Kushtia, because it was championed by the Mayor. Generally, political will is lacking because elected leaders are not keen to increase tariffs or impose taxes, yet OPEX of services needs to be covered.

The present mechanical system is too large to access slums. A smaller alternative is needed, meaning that the number of mechanical transports will increase.

Study on Willingness to Pay for Safe Emptying Services

The ‘willingness to pay’ study on safe emptying services aimed to research what consumers find as an acceptable fee for safe faecal sludge emptying services, possible tariff structures and the possible roles of service providers in sustaining, operating and maintaining these services. This research showed that consumers were willing to pay a higher price if the service would be efficient and effective.

Pilot services with fees varying from 7.50 euro (BDT 750) to 10 euro (BDT 1000) were conducted, and customers in core city areas were paying without any hesitation. This encouraged us to increase the price of emptying from 5 euro (BDT 500) to 10 euro (BDT 1000) for a 1000 litre Vacutug emptying service.

The positive financial outcome showed that a viable business case for faecal sludge services was possible, as we all know that money can make dirty business glamorous.

Study on Market Acceptance of Co-compost

The market acceptance of the co-compost in Kushtia Pourashava was studied with the following scopes of work: (i) To analyse the market acceptability of co-compost, (ii) to improve the marketability of co-compost, and (iii) to propose an optimum price for the product co-compost. Both primary and secondary data were used to accomplish these scopes of work. Primary data were collected from four different Upazilas in the Kushtia district, through a field survey with structured questionnaires along with checklists for Focussed Group Discussions and Key Informant Interviews. The study revealed that there is demand for compost, especially from large-scale producers.

The above formative research and willingness to pay findings were used to develop a practical behaviour change development strategy.

[1] Traditional approaches to improving sanitation, which are aimed at building facilities, have not resulted in significant and sustained sanitation coverage. More promising strategies have focused on creating demand for improved sanitation by changing behaviors, while strengthening the availability of supporting products and services. The objective of this framework is to analyse sanitation behaviors to design effective sanitation programmes and the implementation of sanitation promotion interventions.

1.3 Behaviour change communication (BCC) strategy

During the first stage, and based on the formative research we decided to focus on safe desludging, and to try change two major barriers for safe desludging: the perception that desludging is a hassle, and public unawareness of a safe service. Latrines with functioning twin pits and pit toilet containment were discussed during orientation meetings and public gatherings.

The preparation of the BCC was led by the Khulna City Corporation (KCC) Health Officer to ensure ownership of the government. This route took implementation more time because BCC was a new topic to stakeholders, but eventually relevant officials embraced the importance of this evidence based approach. Once this approach was adopted, we developed messages, materials, media, defined annual targets, and set up a monitoring plan. Finally the BCC strategy was endorsed by the Standing Committee of Waste Management, and approved by the City Council in Khulna.

1.4 BCC campaign: authorities clearly communicate the rules of the game, and make it easy to act upon them.

Based on the BCC Strategy, the city corporation of Khulna developed a campaign that focused on the main message of safe and regular emptying of faecal sludge with the main tagline: ‘Empty your septic tank every year!’. The main aim of the campaign was to trigger citizens into action. Various media like drama, songs, leaflets, talk shows, and a quiz competition were used to repeat the same imperative over and over of Empty your septic tank every year!

A press conference led by the Mayor himself was organised, and around 60 local journalists participated, ensuring wide media coverage in the following days. During this launch event more than 1500 citizens participated. The launch was followed by a four-month campaign with various events in every slum under the leadership of local Ward Councillors.

Read the previous chapter - introduction

Read further about this project:

Component 2 - Safe and affordable sanitation services

Component 3 - Governance, regulations and enforcement

Component 4 - Treatment, disposal and reuse

Figure 1: Honourable Mayor launching the awareness campaign logo.

Figure 2: Community gathering in one of the informal settlements.