The climate crisis and the UN's new agenda for peace

As world leaders gather for the upcoming United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) and Climate Week, climate change and global peace intersect.

The New Agenda for Peace, published in July, links climate, peace, and security. In this article, we delve into the profound link between climate and peace, exploring the challenges faced by fragile contexts and the critical role organisations like SNV play in addressing these interconnected crises.

The complex intersection of climate and conflict

July 2023 was most likely the Earth's hottest month on record. UN Secretary-General António Guterres said: 'The era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling has arrived… climate change is here. It is terrifying. And it is just the beginning.'

Scientific experts report extreme sea temperatures in the North Atlantic, a once per-2.7-million-year event in Antarctic ice and heat domes on different continents.

Persistent drought in the Horn of Africa is undoubtedly driven by climate change. And there is a 'vicious cycle of climate change and armed conflict' in the Sahel. The UN thinks, for example, that 100,000 hectares of arable land are lost to desert annually in Niger. Such desertification is one concern amongst many more evident drivers in this country, the latest in the region to experience a military coup.

An astonishing 600 million people are already living outside the 'human climate niche,' and the most vulnerable individuals, those with the least power and the fewest resources, are bearing the brunt of this crisis. Given this stark reality, what decisive action can we take in the face of this urgent global challenge?

Haste in the North, greater needs unmet in the South

Policymakers and investors in the global North are racing to manage climate risk (whilst going slow on emissions reductions). Yet, for years, SNV has seen the impacts in the most climate-vulnerable contexts, such as the Sahel, the Horn of Africa, and South-East Asia.

The impacts are felt through effects on water quality/availability and land degradation, directly affecting food insecurity, a key driver of conflict. Fragile contexts also often experience the highest recurrence of extreme climate events like floods, droughts, and high temperatures.

Impacts exacerbate existing inequalities relating to gender and processes which marginalise people. Addressing these impacts to support peace and stability (and reduce inequalities) in these regions is critical for the communities living there and in the interests of neighbouring countries, trading partners, and investors.

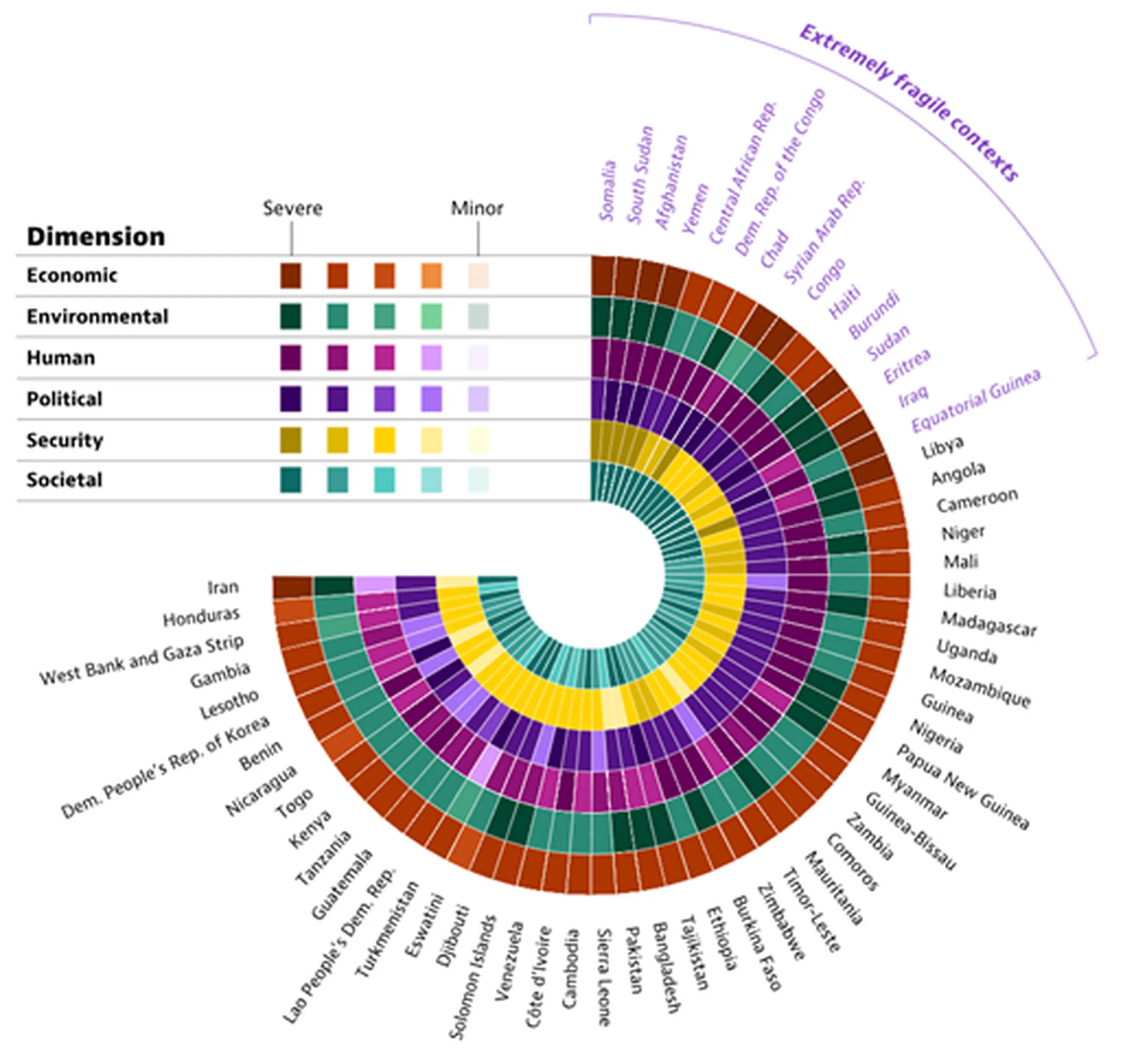

OECD's Multidimensional Fragility Framework. OECD States of Fragility

Of the 60 fragile contexts tracked by the OECD, 15 are categorised as being extremely fragile in 2022, with nine of these showing extreme intensity on the environmental dimension.

Fragile contexts like Niger are home to 1.9 billion people, 24% of the world's population. However, by 2022 73% of the global population living in extreme poverty also lived in these places.This figure could surge to 86% by 2030.

There are profound challenges to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in these settings. But complexity should not stop us from finding ways to support people to adapt to impacts for which they are not responsible.

The impact of the climate crisis depends heavily on how states are governed and how climate-induced competition is managed. In addition to addressing climate shocks, we must increasingly focus on strengthening the ability of states to withstand those shocks and ensure the resilience of their most vulnerable communities.

Above all, mechanisms are needed to regulate access to resources within or among states peacefully. It is also crucial that international development projects ensure their actions reduce rather than exacerbate divisions.

Meanwhile, annual adaptation costs for developing economies will be USD 155 to USD 330 billion by 2030. Yet in 2020, only $28 billion was provided. And the more fragile a country is, the less climate finance it has historically received.

Extremely fragile states averaged $2.1 per person in adaptation financing compared to $161.7 per person for non-fragile states.

This unacceptably low level is because climate funders have a low-risk appetite and tolerance for working in fragile and conflict-affected situations. Protocols also hinder adaptive implementation and delivery. Data and travel restrictions make managing and monitoring projects difficult, too.

Adapting to a changing climate

SNV has been working innovatively with technology and private partners, for instance, using satellite data to directly support the herd migration decisions of pastoralists in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. This helps them adapt to a changing climate: failing rains, more floods, higher peak temperatures, and increased water scarcity.

Supported by the Dutch Government, the €100 million Pro-ARIDES programme aims to contribute to increased resilience, food security, and incomes of farmer and (agro)pastoralist households – 2.1 million people - over ten years in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger.

We also help accelerate the low carbon transition while supporting SDG 7 – the UN goal of Sustainable Energy for All. Since 2020, in Mozambique, the BRILHO programme has supported 24 companies, leveraged over €25 million in private-sector funding and benefited over 1.1 million people who now have sustainable rural energy access.

Around 0.7 million people in 18 countries gained access to water, sanitation, and hygiene services through SNV projects in 2022, for example, through The Eau, CLE du Développement Durable (ECDD) project ('Water, the key to sustainable development'). This supports the Permanent Secretariat and the other partners in the sustainable management and use of water resources in Burkina Faso.

And on financing to leverage the private sector, in our role co-managing the Origination Facility of the Dutch Fund for Climate and Development we see ways to support investment in companies doing business in challenging contexts, improving resilience in food systems, energy and water.

Bridging the climate gap: advancing climate adaptation finance

While the UN's New Agenda for Peace and its proposal to establish a new funding window within the Peacebuilding Fund for more risk-tolerant climate finance investments is welcomed, and SNV stands ready to support the proposed regional and sub-regional hubs on climate, peace, and security. More can be done now to bring climate finance support to people in most need.

Climate adaptation funding in FCS contexts should be increased, and this can be done by:

Approaching risk differently in FCS to enable climate adaptation financing – programmes must be more adaptive and risk-tolerant by design. For example, public-private partnerships are decisive and appropriate to overcome the risk of innovation aversion, but they should have a long-term vision and commitment designed for maximising impact and inclusive outcomes;

Addressing structures ("silos") that impede informed action – systems change is needed, raising awareness, expanding partnerships with inclusive local civil society groups and maximising synergies rather than trade-offs between water, energy, and agri-food systems to support resilience; and

Providing both smaller and larger scale support and with diverse partners - optimising collaboration between all stakeholders. This should include the smart use of technologies such as digital climate adaptation services. These have enormous potential to diagnose vulnerability, enabling decision support systems and opportunities for digitally enabled micro-credits. This way, we can apply scale-neutral climate adaptation options, primarily to support pastoralists and smallholder farmers.

We note that the United Arab Emirates COP28 presidency focuses on accelerated climate action and finance in FCS, particularly on adaptation, preventing and addressing loss and damage, and is preparing initiatives to launch at COP28.

What more needs to be done

Beyond adaptation, the Loss and Damage Fund (LDF) agreed at COP27 in Egypt must deliver climate justice to affected communities. The Transitional Committee should:

Learn from existing funds like the Green Climate Fund and enable faster and more comprehensive responses to Loss and Damage, including avoiding lengthy administrative hurdles and

Find ways to serve the needs and priorities of the most vulnerable and marginalised communities facing losses and damages, including women and girls and pastoralists.

The case is stronger than ever to directly support communities most affected by climate extremes; it is in all our interests.