Strong institutions - the magic ingredient for water security?

How can we turn the rhetoric of #TogetherForImplementation into action and take concerted steps toward our water and food security?

Read Impressions of COP 27 by Dr Sonja Hofbauer, Global Technical Advisor – Water Supply Services, SNV.

‘More adaptation investment is needed’ was among the key catchphrases coming out of COP 27. Amid the loud calls to upgrade or build climate-resilient water and wastewater infrastructure, few raised the need for collective stocktaking and joint decision-making – over our limited water resources with inherent challenges in quantity (especially quality) and the many different purposes we need water for. As greater water demands are being made to enhance food and biofuel production and implement carbon storage, it is crucial that we begin adopting a holistic approach to achieving water security for all. Building strong institutions probably holds the key to this.

Henk Ovink, Special Envoy for International Waters Affairs, The Netherlands, expressed concern over the many water bodies already at their ‘tipping point’ and how the water sector was being looked at to fix the problem.

Jean de Matha, Programme Manager of the Drylands Sahel Programme, SNV in Niger, emphasised the urgency for the world to come together to protect our vulnerable water systems. He stressed the need to focus on water quantity and quality to mitigate the effects of floods and droughts and secure access to clean water – for agricultural use and human consumption.

Barbara Pompili, Chair of the OECD Water Governance Initiative lamented that water governance [1] is lacking – particularly regarding groundwater – leading to overuse and possible tensions.

Some weeks ago, it was announced that the world’s population reached the 8-billion mark. We live in worrying times. We face multiple intersecting crises: climate change, food insecurity, and water insecurity. With 3.2 billion people already living in agricultural areas with high water shortages, we know that the most vulnerable people are at the front lines of climate-aggravated food and water scarcity.

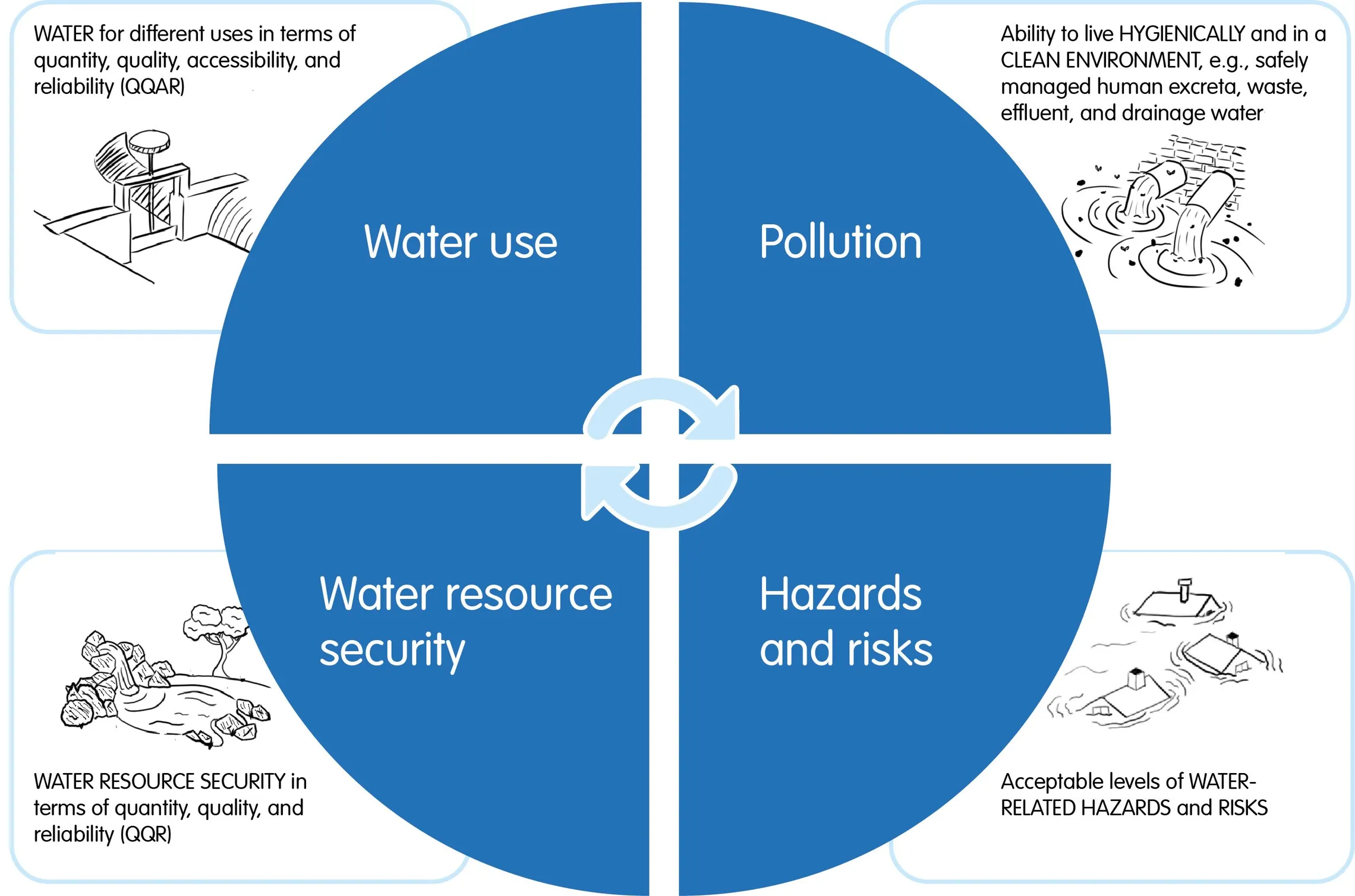

Water security dimensions, SNV

Towards better-governed water resources and use

For SNV and like-minded partners, institutional strengthening is a key ingredient to realise better-governed water resources and use. Strong institutions, in our view, could help balance competing water use while preserving water quality and ensuring its sustained availability.

Below are some points that could help us strengthen our institutions – #TogetherForImplementation – for our water and food security.

Create a comprehensive sector architecture with adequate legal and policy frameworks. Karim Ehab Salah, Egypt’s youth representative at COP 27 said during the Water Pavilion closing session that we can’t rely on goodwill alone… there must be laws guiding the implementation of the SDGs – a statement that many water sector professionals agreed with. For the sector, such an architecture will need to: (i) include explicit procedures that allow modifications to the legal and policy framework to ensure applicability to our changing times, (ii) be complemented by the necessary resources for implementation and continuous framework engagement/review, and (iii) be built on a strong foundation of political will; as has been testified by Honduras waster sector representatives and the recent 100% improved sanitation success of Bhutan.

Set in place strong and inclusive sector institutions built on the foundations of (i) broad participation involving women and traditionally marginalised groups in the decision-making process to enable a dialogue over conflicting water resource demands, (ii) evidence-based decision-making processes that consider resource sustainability and the impact of all big and small uses, (iii) enhanced monitoring systems and practice, using data to inform forward-looking plans, adjustments, and regulation decisions, e.g., allocation of permits, and (iv) clear systems of checks and balances that safeguard the water resource base and protect it from pollution to reduce the impact of water-related disasters. In a world where loan funding places a bigger focus on physical development, Dr Callist Tindimuga, Commissioner for Water Resources Planning and Regulation in Uganda challenged the sector to weave components of data and evidence gathering and institutional capacity strengthening into loan projects.

Speakers at the Water data for planning and monitoring in the Food Pavilion (Greenhouse Agency)

SNV's Jean de Matha talking about Garbal, a satellite-based water service detection for pastoralists (Greenhouse Agency)

Enhance inter-sectoral/departmental collaboration. Omar Zayed, Acting Director General of Water Resources Directorate, Palestinian Water Authority, shared an example of successful collaboration between the country’s water and agricultural departments’ monitoring of water bodies and usage. As a result of this partnership, Palestine’s farming/agricultural communities started to use treated wastewater for crop growth, contributing to the protection of the country’s dwindling groundwater sources. Working together across sectors is required to attain water security but strong institutions to facilitate such collaboration is needed – from creating the required standards and guidelines to developing coherent guidance that enables all sectors to speak with one voice.

Lift the missing middle. Institutional collaboration is often focused on the national level or the lowest levels of governance – community-based institutions. Local and regional governments are often missing in this equation. In Kenya, James Mwangi, Nexus Coordinator, SNV in Kenya, shared how strong sector voices at county level led to improved accountability and strengthened institutional capacity for inclusive climate resilience. As part of the missing middle, Dr Callist Tindimuga advised for catchment-based approaches in Uganda to be spearheaded by catchment management organisations, whom he considers as most suitable in bringing all stakeholder groups together to navigate the challenges of competing water uses and agree on a plan jointly that addresses everybody’s interests, including the ecosystems’.

Community borehole drilling in Mozambique (SNV and PRONASAR)

GESI assessment at the Phoksundo Suligaad watershed, Nepal (SNV)

No climate adaptation in a water-insecure world

The assertions above do not call for a complete shift of investments into institutional strengthening. Of course, we will still need investments in infrastructure that is innovative, climate-resilient, and fit for changes in the future. Just like everything else in life, we must strike a balance. The future of humanity, our water, our food and nutrition, and peace, rely on achieving a balance in needs – ‘between people, between current and future generations, and between humans and the environment.’

Quoting Joe Ray, Senior Advisor, Valuing Water Initiative, Netherlands Enterprise Agency, during the session, Climate-Aggravated Water Scarcity as a Food Security Issue, ‘Without water security there is no gender equality, no economic growth, no climate adaptation. But if we learn to value and govern water in the right way, water becomes the enabler of all sustainable development goals. We gain better jobs and cleaner growth, secure food systems, achieve more resilient cities, and increase our biodiversity.’

Clearly, my impressions convey that there are no quick fixes. But we do have hard and evidence-based work to help us spur into action, #TogetherForImplementation. Unlike projects that end and administrations that change, strong institutions – coupled with political will – are more long-lasting.

More information

[1] As per the OECD definition, water governance refers to the range of political, institutional and administrative rules, practices and processes (formal and informal) through which decisions are taken and implemented, stakeholders can articulate their interests and have their concerns considered, and decision-makers are held accountable for water management.

[2] Read short SNV COP 27 reflections on water, agri-food, and energy here.