Civil society contributes to local food and nutrition security framework (Story of Change)

In Honduras, civil society organisations increased advocacy space at the local level by establishing a local framework complimentary to the official food and nutrition security (FNS) framework. Known as municipal FNS ‘tables’, these are effectively multi-stakeholder platforms, to create awareness about the main results of FNS studies and influence municipal authorities in favour of FNS local policies and budget allocation and to scale these up to higher levels.

You would think that they had known each other forever. Their engagement and activity at all times of day and all days of the week is astounding. This community cares about each other deeply and has been working together closely… yet it was only in 2016 that their work truly began.

This story follows the journey of several civil society organisations on the path to improved food and nutrition security across Honduras. From identifying gaps in data and policy and legal frameworks, to generating evidence and reviving local consultative spaces complimentary to the official FNS framework, this is the story of how CSOs increased civil society space at the local level and brought grassroots voices to the fore.

The problem: food and nutrition insecurity

In Honduras, food and nutrition insecurity is fuelled by high rates of poverty. 67.11% of the population lives below the poverty line, with 42.87% living in extreme poverty (study by FOSDEH).

Policy, legal framework and data gaps

The FNS problem is fuelled by gaps in the country’s policy and legal frameworks. Before 2016, there were some policies and legal frameworks, but some were outdated and others were not implemented.

Honduras’s FNS framework is fed by national and regional bodies known as mesas (tables). These mesas are consultative spaces where the government invites institutional actors to identify and address the FNS situation in Honduras.

Yet there was a gap at the local level, as no such mesas existed to feed the regional and national bodies. The voices of those directly affected – community members, youth and women’s movements and local governments – were not heard. This means there was a lack of understanding of the reality on the ground - including gaps related to research-based data and evidence, characterised by the lack of updated data on nutrition status in general. This resulted in a lack of an integrated approach to FNS; lack of accountability, not much space for CSOs to address the issue, poor integration of private sector, and inadequate budgetary allocation.

According to Mr. José Ramón Avila, the immediate context prior to the entry of the V4CP in which the CSOs operated was very adverse, conceptually distorted and affected by improper practices in the exercise of public administration, with few spaces to influence.

In addition to the policy and legal framework gaps, there was a lack of available data on food insecurity, which made the CSOs’ work particularly difficult.

Programme response: action at the local level

V4CP CSOs realised, through stakeholder analysis and the development of clear advocacy plans, that their added value could have more impact at local level, connecting their expertise, evidence and efforts with new local leaderships such as women and youth networks.

Evidence generation

Their first step was thus to generate evidence to back up their claims. Upon the CSOs’ request, IFPRI produced several documents that clearly synthesised complex data on the situation of FNS in the country. These included data on government’s budgets and investments in FNS, and were used at various seminars and municipal tables to highlight the gravity of the situation.

Local advocacy through municipal tables

It was during a V4CP workshop that CSOs asked themselves, how can we highlight the rich expertise of local grassroots actors in a meaningful way?

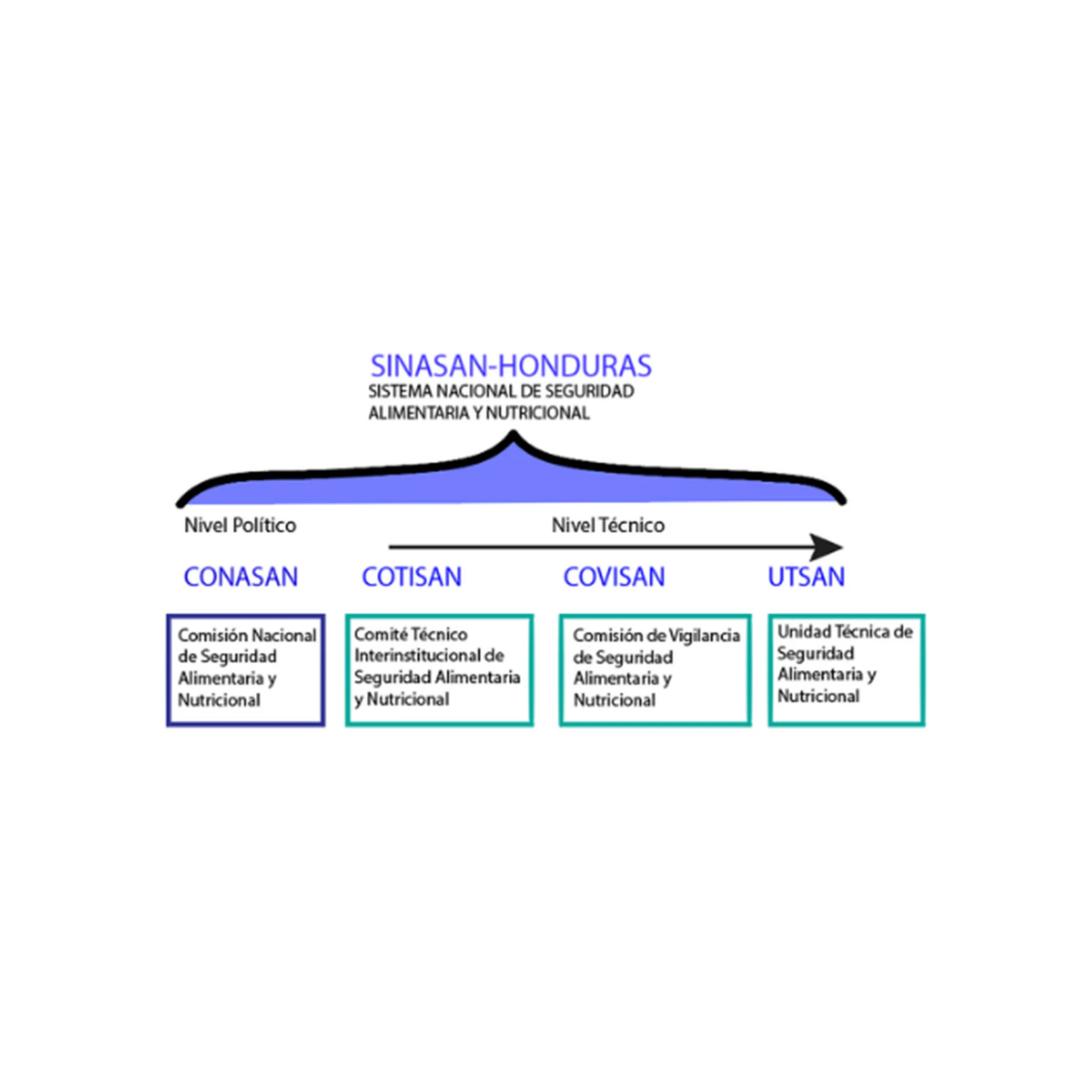

They decided to focus on the FNS tables, applying a strategy that included the creation of municipal FNS roundtables, reactivation and strengthening of dormant “mesas municipales SAN” (municipal FNS roundtables), which exist within the legal framework but had not been active since 2010.The figure below depicts the national food and nutrition security system of Honduras, spanning from political to technical level and consisting of several bodies: CONASAN (National Commission for FNS); COTISAN (Technical Interinstitutional Committee for FNS); COVISAN (Surveillance commission for FNS); and UTSAN (Technical Unit for FNS).

National food and nutrition security system of Honduras.

According to Mr. Ramón Avila, “the municipal tables are an expression of local work, from the ground, where producers as social forces are promoting and driving the agenda, who invite local authorities to discuss the food and nutrition security situation.”

This is key to rectifying the effects of a top-down approach. According to Gedberth, the problem with public programmes is that they are not conceived under an integral FNS approach, they do not cover all aspects such as accessibility, availability, etc., they are short term and punctual actions, and there is no focus on sustainability. “[The public policies] come to solve hunger emergencies, but do not teach people how to be self-sustainable in terms of food."

The people who participate in the mesas are residents in the communities, and although they may have different approaches to the problems they share, they also have in common the culture, the climate, the majority are poor, with basic education and small subsistence plots in which they grow corn, beans, bananas, yucca, ayote and malanga.

The mesas municipales ensure that communities develop context-specific policies that are integrated at the municipal level. They have strategic and work plans and are formally structured. While these mesas do not have official government recognition, they are locally respected and have built their legitimacy in this way.

Scaling up

While each individual mesa holds legitimacy, their success is also based on successful scaling across the country. The mesas have built up a network across different regions, reinforcing each other. Even though the network had its first meeting in November 2019, CSOs consider that the movement will gather force and will succeed in influencing the regional and national levels.

The change

The change that the local level mesas have brought has been significant. There are now spaces where grassroots voices are included and considered in the formation of food and nutrition security policies.

There is a very high rate of participation of women (in some places up to 70%) and to a lesser extent, youth, at the mesas, ensuring inclusivity in policy creation and decision making. Examples of this are the participatory processes facilitated by partner CSOs ASONOG (Asociación de Organismos No Gubernamentales), RDS-H (Red de Desarrollo Sostenible – Honduras) and CDH (Centro de Desarrollo Humano) for the development and approval of Municipal FNS Policies. Also, some such as ASONOG collaborate with local government in some municipalities on accountability mechanisms. For Jesús Garza the instalment and strengthening of the COVISAN (Surveillance Commission) and the integration of four partner CSOs in it, is a good step in the fight for transparency and accountability in the FNS system.

For Adelina Vasquez, through V4CP, CSOs extended their scope from very local work with farmers and other grassroots groups, to the regional and national context. Her aspiration is to have more CSOs represented at regional tables and in CONASAN, as well as to have an effective process of decentralisation of the FNS (functions and budget) that links the local with the regional and national levels.

For Ávila, capacity building by the V4CP has allowed ASONOG to influence the government agenda, bringing public agendas closer to those of CSOs which were previously separated.

Change is now manifested in the fact that the country has a national instrument, the FNS Policy and Strategy (PyENSAN), which filled a legal gap and took into account some of the CSOs’ contributions.

How will this bring change to the greater context?

The creation of mesas municipales and their scaling across multiple municipalities has had an impact at the local level but will also trickle up to regional and even national levels to influence FNS policies across Honduras.

Strengthened CSOs

Another benefit of the process is that several CSOs have noted how the V4CP programme has substantially strengthened their organisations. It has helped them to work together, create alliances, and raise their profiles. They are increasingly invited to represent civil society in important meetings and events. According to Adelina Vásquez from CDH, “Without the support of the V4CP, obtaining this change would have been difficult, since it was customary to work for livelihoods and not politics, limiting the actions of CSOs at the local level, mainly”.

Conclusion

The experiences from Honduras demonstrate the importance of a strong civil society in influencing inclusive policy making: it is possible to enrich FNS policy through advocacy at the local level. From the local level, where public services are provided and programmes are executed, it is possible to identify their lack of coordination with an overarching FNS policy. The CSOs are committed to advocate for the improvement of the food and nutrition security situation in Honduras, and these are promising first steps in the right direction.

Who we are

The Voice for Change Partnership (V4CP) strengthens the capacities of CSOs to foster collaboration among relevant stakeholders, influence agenda-setting and hold the government and private sector accountable for their promises and actions. It is funded by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs

V4CP meeting with UTSAN, national technical unit on FNS.